The spring of 2017 brought the first of two trips to Europe for me this year. My previous post shared my experiences at two of Poland’s best known zoos. This post explores two of England’s most beloved zoos, London and Chester Zoos. Having a few long-time friends from England, I’ve been lucky to spend quite a bit of time in this beautiful country. I’ve visited the south west region several times (visiting Paignton Zoo and Eden Project in the late 1990s), but as many times as I have fallen in love with London, I had never once visited the famed Zoological Society of London’s crown jewel, London Zoo. The experience of visiting the London Zoo and the Chester Zoo back-to-back allowed for some stark contrasts and very few, but very key, parallels indicating the strong trend of Euro zoo evolution toward immersive storytelling.

Let’s begin in London.

London Zoo is considered the world’s oldest zoo still in existence, having opened in 1828 in Regent’s Park in the heart of metropolitan London. It is an urban escape, and still boasts a wide-open park-like green where modern zoo-goers picnic alongside the zoo’s retro airstream BBQ food trailers.

However, the London Zoo suffers from the constraints of its past. As would be expected in such a historical city, older buildings are closely protected and preserved as historic monuments--and therefore untouchable for demolition or adaptive reuse (structures can be maintained and repainted, but only in the original palette of colors!). The world’s first aquarium still functions on grounds, and the infamous modernist penguin exhibit that is commonly held as the standard of how not to design an exhibit, remains empty and untouched. The Zoo is also terribly landlocked, and with its historic structures, its site is a patchwork of small pockets of land available for new attractions.

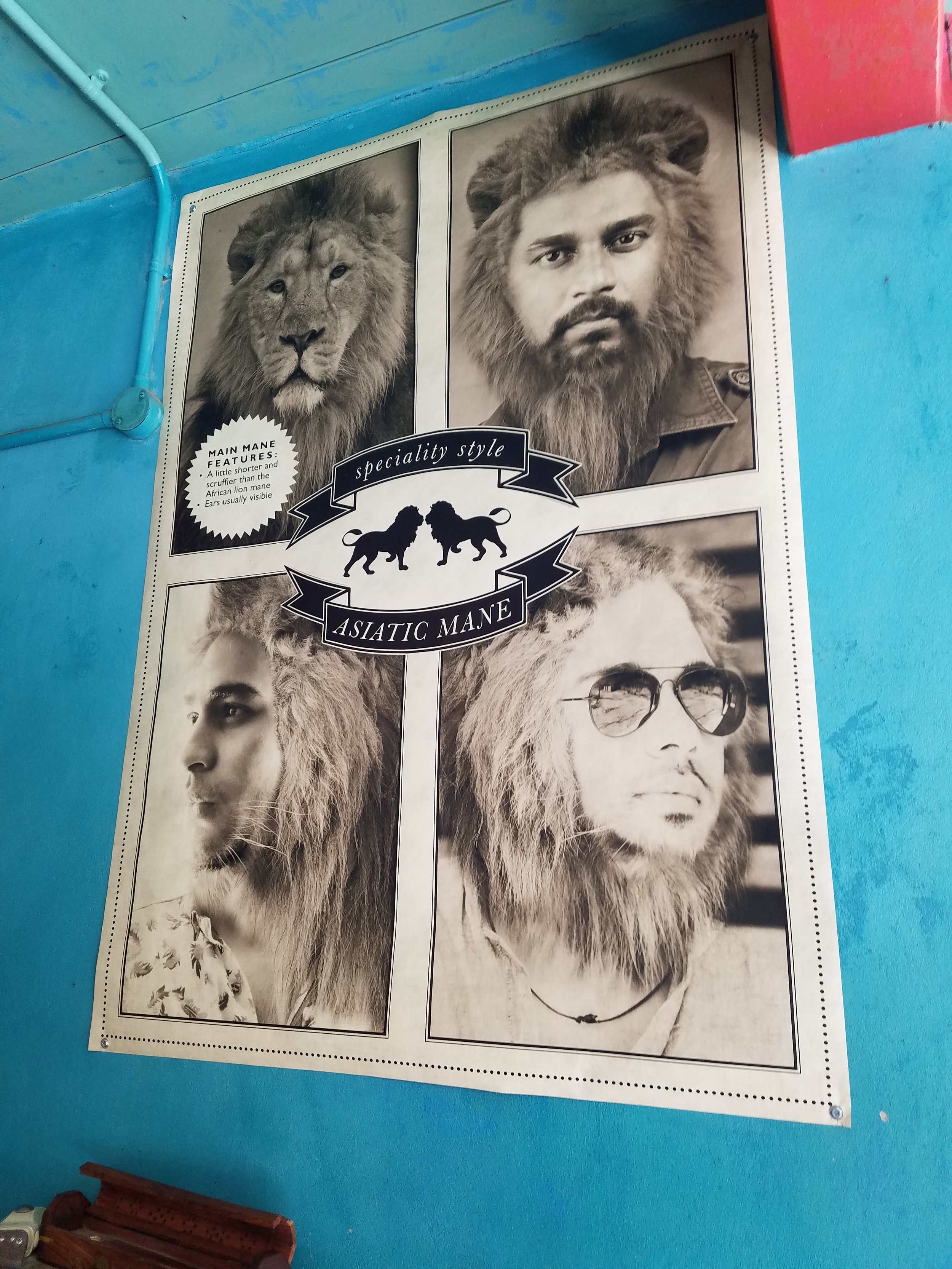

But given these constraints (and perhaps because of these constraints), the Zoo can and should be considered one of the world’s best, with moments of experiential brilliance to  rival any. The relatively new Land of the Lions was a small budget (under $10,000,000 USD) renovation and expansion that weaves visitors through a fully immersive story of conflict between Asiatic lions and the ever-expanding population centers of India. Thematic architecture is used as lion barriers and blurs the lines of people and animal spaces. And, educational moments (probably the most clever part of the entire experience) are disguised as theming. A barber shop that teaches about lions’ manes. A seamstress kiosk that shows us the biological difference between Asiatic and other lions. It’s a place to explore and be surprised, and although the immersion is heavily skewed to a human dominated space, the lions’ habitat feels natural and appropriate.

rival any. The relatively new Land of the Lions was a small budget (under $10,000,000 USD) renovation and expansion that weaves visitors through a fully immersive story of conflict between Asiatic lions and the ever-expanding population centers of India. Thematic architecture is used as lion barriers and blurs the lines of people and animal spaces. And, educational moments (probably the most clever part of the entire experience) are disguised as theming. A barber shop that teaches about lions’ manes. A seamstress kiosk that shows us the biological difference between Asiatic and other lions. It’s a place to explore and be surprised, and although the immersion is heavily skewed to a human dominated space, the lions’ habitat feels natural and appropriate.

As good as the Land of the Lions is, my favorite piece at the London Zoo was a thematic overlay to the historic bird house. The Victorian building, originally built as a reptile house in 1883, was renovated at some point to include multiple small bird flight cages as  well as a relatively small walk-through aviary. What seemed to be a more recent renovation implemented a fairly simple graphic overlay. The striking part of the renovation was the intentional decision to embrace the building’s heritage, instead of trying to hide it. The graphic overlay features Victorian styled artwork highlighting the beauty of birds, including ingenious classic silhouette art of several recognizable bird species, as well as the use of “wrought iron” rails and benches traditionally associated with this time period. I loved the intent and the impact of this small project, but I would’ve loved to see this story implemented on a larger scale—redesigning the cages themselves to be highly ornate bird cages we would’ve seen in this era. What a platform to introduce the concept of “where we’ve been, and where we’re going” in terms of zoos, as well as our society’s evolution in regards to our relationship with animals.

well as a relatively small walk-through aviary. What seemed to be a more recent renovation implemented a fairly simple graphic overlay. The striking part of the renovation was the intentional decision to embrace the building’s heritage, instead of trying to hide it. The graphic overlay features Victorian styled artwork highlighting the beauty of birds, including ingenious classic silhouette art of several recognizable bird species, as well as the use of “wrought iron” rails and benches traditionally associated with this time period. I loved the intent and the impact of this small project, but I would’ve loved to see this story implemented on a larger scale—redesigning the cages themselves to be highly ornate bird cages we would’ve seen in this era. What a platform to introduce the concept of “where we’ve been, and where we’re going” in terms of zoos, as well as our society’s evolution in regards to our relationship with animals.

In contrast to the urban, historical zoo experience of London Zoo, Chester Zoo is large, sprawling, and reflective of the English countryside in which it resides. Located about an hour outside of Manchester in the north of England, in a “posh” suburb with lots of football money (according to my Brit friends!), the Zoo is a relative newcomer, having opened in 1931. Despite its age (which relative to American zoos is quite old), the Zoo--unlike at London--is not restricted by historic facilities nor is it landlocked. Its oldest building still in use is the forgettable Aquarium from the 1950s.

The Zoo may be best known for its participation in several television series since the turn of the new century, but its most impressive exhibit experience is the new Islands at Chester Zoo project. Phase 3 of the project is expected to open in 2018, but the bulk of the exhibits focused on tropical Asia where the zoo is heavily involved in conservation, opened in 2015. The massive exhibit area expanded the zoo by 15 acres and includes tigers, orangutans, visayan pigs, birds, and much more anchored by the visually impressive river boat ride. Although I personally am les s than enthusiastic about boat rides to see animals (and I didn’t get to ride this one—out of season), the aesthetic of the river running through the exhibit experience was impressive and added a lot to the immersive setting. Although visitors begin their journey through Islands in a fishing village, and eat at a large Balinese (?) building, the bulk of the exhibit is landscape immersion, rather than cultural immersion, with limited props providing a hint of location specificity. The orang exhibit featured a research hut with jewel exhibits and educational features hidden expertly amongst theming.

s than enthusiastic about boat rides to see animals (and I didn’t get to ride this one—out of season), the aesthetic of the river running through the exhibit experience was impressive and added a lot to the immersive setting. Although visitors begin their journey through Islands in a fishing village, and eat at a large Balinese (?) building, the bulk of the exhibit is landscape immersion, rather than cultural immersion, with limited props providing a hint of location specificity. The orang exhibit featured a research hut with jewel exhibits and educational features hidden expertly amongst theming.

Chester Zoo was created with the intent to eliminate bars typical of Victorian zoos, like London Zoo. So, while many of the oldest exhibits definitely feel outdated, most are broadly sweeping with shared landscape views unimpeded by visual disruptions. The Zoo overall feels like a walk through the countryside or even a quiet park in a small town. The few wide promenades that remain, dotted with generic exhibits like storefronts, are tucked away and non-intrusive. This zoo, more than any other that I have visited in Europe, felt most like the American zoos that we have come to know and love.

The thing that REALLY sets Chester Zoo apart, making it one of the world’s best zoos, is its incredibly strong message of conservation. The dedication to branding and message at this zoo is unlike any I’ve seen. A visual continuity through font and graphic style ties the  “Zoo Message” (as I call it) throughout the various exhibits, while still incorporating a sense of place within each exhibit through independently styled graphics and props. The Zoo Message is reinforced through small moments (like a pollinator garden along a viewing rail), eye-catching signage, videos, and even a book that can be purchased at the gift shop. What’s most important about Chester’s messaging style is that it is always approachable (visually and content-wise) and embraces family and fun with a touch of whimsy and humor. A great lesson to be remembered, because, as we know, people come to zoos (and aquariums) for a fun time that makes them feel good about spending their precious resources (of time and money).

“Zoo Message” (as I call it) throughout the various exhibits, while still incorporating a sense of place within each exhibit through independently styled graphics and props. The Zoo Message is reinforced through small moments (like a pollinator garden along a viewing rail), eye-catching signage, videos, and even a book that can be purchased at the gift shop. What’s most important about Chester’s messaging style is that it is always approachable (visually and content-wise) and embraces family and fun with a touch of whimsy and humor. A great lesson to be remembered, because, as we know, people come to zoos (and aquariums) for a fun time that makes them feel good about spending their precious resources (of time and money).

Get yourself to England to check out both of these incredible zoos!

Get yourself to England to check out both of these incredible zoos!