My company is just me. And that’s by design. I do not intend to hire employees and I purposefully keep my fees and client volume low. I view it as a complete success, but given the common perception of “business success,” I often wonder if others would agree… In this article, I outline my business strategy of Growing Small as an alternate measure of success.

Tips for Working with Introverted Consultants

Who CHANGE the world? Girls.

As a single 40-something who consciously chose cats over kids, I know my limitations when it comes to understanding the intricacies of childhood learning. You might see this as a challenge for a zoo designer, but I guess I just always thought about designing experiences that hit the emotional wire that runs through each of us, regardless of age, sparking that special connection people have with animals. I’ve never been a believer in heavy informational signage, hoping that emotional connection will instead drive people to google (verb) their newly found favorite animal.

Yesterday, I discovered this fascinating new study that shows the best way to convince an adult of an argument (specifically, in this study, related to climate change) is to get their kids to make the argument for you. And, if they have a daughter, all the better, because as we ALL know, girls are better at communication and deep thinking (no haters…the study says this!).

The implications of this study to zoos and aquariums are immense. The study, in general, provides yet more evidential support of zoo and aquarium experiences being critically important. Not only do we have the opportunity to connect with people of all ages EMOTIONALLY, but we’ve now unlocked the key to impacting the minds and possibly the actions of adults, too. We already assumed children were sponges of information (if they are interested in a subject), but now we know the importance of those sponges—beyond building the foundation of thoughtful, empathetic, conservation-minded future adults. Those sponges could be the perfect delivery mechanisms for conservation change for today’s adults. They say you can’t teach an old dog new tricks. The question is now, does that dog have a daughter?

The study showed that not only are daughters better at convincing parents, but daughters are better specifically at convincing dear old dad. I wonder if there is an age limit, because the nostalgia of a blond, buck-toothed, bespectacled pre-teen in a pink polka-dotted dress dancing on dad’s size 15 shoes at the daddy-daughter dance is a powerful tonic egging me on to attempt to break through dad’s climate change denial built up from endless hours of FOX News viewing. I’ll let you know if I change his mind.

In the meantime, take a look at the study, summarized in Scientific American here, and let’s work on connecting the informational dots between emotional, inspiring experiences and what everyday people can do to make the world a better place for all living things. Including those old dogs…

Happy Anniversary! 10 Years of DesigningZoos.com

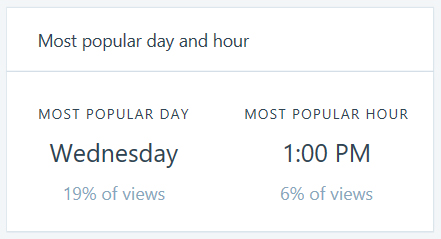

Can you believe this summer marks ten years of my little corner of the internet talking about design and the future of zoos and aquariums? Although my posting has become more infrequent as my professional life has evolved, you--my supportive and sometimes thoughtfully critical reader--remain constant. I owe you a huge Thank You for reading my ramblings, and contributing your thoughts. For funsies, I thought we'd review a few of the highlights from the past 10 years and over 200 posts!

Top Ten All-Time-Most-Popular Posts (by visits)

10. "Visitors: An Overlooked Species at the Zoo" (2013) by guest blogger and colleague, Eileen (Ostermeier) Hill. Discusses the critical importance of visitor studies at zoos, some hurdles to studies, and the role of designers relative to visitor studies.

9. "The Future of Zoos: Blurring the Boundaries" (2014) a second entry by guest blogger and obviously brilliant colleague, Eileen Hill. Powerpoint presentation with script about trends in zoos today and how they may play out into zoos of the future. Eileen proposes zoos of the future will by hybrids of multiple science based institutions.

8. "St. Louis Zoo's SEA LION SOUND" (2012). Showcasing the then-new exhibit at the Zoo including fly-thru video, photos of new exhibit, and interview with one of the architects from PGAV Destinations who helped bring the design into reality.

7. "SAFARI AFRICA! Revealed at Columbus Zoo" (2012). Announcement of the ground-breaking of the eventual AZA Top Honors in Design award-winning Heart of Africa (renamed). Includes renderings and site plan.

6. "Underdogs: The Appeal of the Small Zoo" (2013). Exploration of what makes small zoos so appealing to visitors, and meaningful to work for as a designer. Features Binder Park Zoo, Central Florida Zoo, and Big Bear Alpine Zoo.

5. "In Marius' Honor" (2014) by guest blogger and now Project Manager at the esteemed Monterey Bay Aquarium, Trisha Crowe. Trisha explores her emotional reaction to the Copenhagen Zoo's disposal of Marius the giraffe, and implores readers to support zoos, no matter your stance on animal rights.

4. "Small and Sad: Dubai Zoo's Relocation on Hold Again" (2009). Occurred to me today, should have been title "Small and SAND", but the sad state of the old zoo is what made this post so popular. Includes design plans and renderings--which I am sure are woefully out of date. Anyone have any updates??

3. "How to Become a Zoo Designer" (2014). After about 25,000 emails from aspiring zoo designers asking similar questions, I just went ahead and wrote it up to shortcut a step... Still, feel free to email me--I always write back. Let's be pen pals!

2. "The Next Zoo Design Revolution" (2008). One of my very first posts, which explains the popularity. Some say naïve, some say gutsy look at incremental revolution in zoos. The future of zoos has been examined at least 300 times since this one, but in re-reading, I see some kernels of accuracy. Expect an update soon...

And in the #1 spot....

1. "A Quick Lesson in Zoo Design History" (2008). Perhaps my second post ever, which again explains it's number 1 spot. A not-as-advertised look at zoo design history which, I have a feeling, has been referenced by many of the 25,000 students (above) in their zoo projects. Holla at me if you cited me!

Top Ten Recommended Reads for Zoo Designers (aside from those above)

10. "To Safari or Night Safari" (2008). I'm a sucker for the title. But this post examines the very slow to catch on trend of after-hours programming or extended zoo hours as a feasible method to increase attendance. Post-posting amendment: in particular, this is a great strategy for targeting adults without kids.

9. "Does Winter Have to be a Dead Zone at the Zoo?" (2013). I cheated a little on this one. I didn't actually post to DZ.com, but to my blog at Blooloop.com where many of my more recent posts have been landing. This one discusses another strategy to increase attendance by targeting the most difficult time of year for temperate zoos: winter.

8. "Zoo Exhibits in Three Acts" (2011). Storytelling in zoo exhibits, told through, what else?: a story.

7. "8 Characteristics of Brand Experience" (2018). A new one! Understanding what makes strong brands so very strong is important and applicable to new attractions at zoos and aquariums. Examined through the lens of non-zoo brands, like my fav: OrangeTheory.

6. "Interactivity and Zoos" (2013). Examining the different modes of interactivity that are available in zoos, and how they can be applied to experience. A good primer.

5. "How Animal Behavior Drives Zoo Design" (2011). Starting with animals in design can be overwhelming. What information is pertinent to a designer, and what is just interesting to know. Another good primer for learning the basics of zoo design.

4. "Chasing Big Cats: Snow Leopards and Perseverance" (2017). Being a good designer is about so much more than just having cool ideas and being able to communicate them well. Learn the qualities intangible qualities that make good designers, GREAT. Don't be afraid...hint, hint.

3. "Making Responsible Tacos: Conservation Brand Perception at Zoos and Aquariums" (2015). Adapted from a talk I gave, I examine how aspirational brand should translate to experience in zoos and aquariums using the popular taco analogy. Yum. Tacos.

2. "Five Zoo Innovations that have been around for Decades"Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5 (2014). Again, pulled from Blooloop. A series of 5 posts examining design elements and characteristics that American zoos have been implementing for decades. This series was an angry reaction to the 'revolutionary' design of metal pods floating through a zoo in Europe. A woman scorned...publishes 5 posts to prove how you don't know anything about innovation. Ha!

1. "Zoos in a Post Truth World" (2017). What every zoo and aquarium advocate needs to consider in this continued atmosphere of skepticism, critique, and distrust. As a zoo designer, you must be aware of changing perceptions and the power we have to shape them.

Top Ten Things I Learned in the Last Ten Years (Blogging or Otherwise...)

10. I'm not shy; I'm introverted

9. How to poop in a hole while wearing 3 three layers of snow pants

9a. Always pack enough Pepto tabs (at least 2 per day while away)

8. I'm not good at social media (see: 10 years of blogging and 600 Twitter followers, probably mostly for cat pics)

7. And speaking of cats, the rubbery buttons of a TV's remote control makes said remote an easy tool to remove cat hair from sofas and pants

6. I sleep better when flying in Business Class

5. Always pay the extra money to hire movers to load and unload that U-Haul

4. Writing isn't hard. Just start typing and...

3. Confidence

2. I lose all 'adultness' around ice cream and baby animals

1. Zoo and aquarium people are really the best people in the world.

Here's to many more decades of Zoo & Aquarium design!

With love and respect--

Your friend, Stacey

The Power of Partnerships: Zoos Joining Forces with Animal Welfare Organizations

A snippet of my quite controversial post over at Blooloop.com about my naively optimistic wish of eliminating the US vs THEM mentality that has invaded every aspect of our world:

"But my real wish, my dream, is of, “what an amazing world this would be’ if we could all join forces. We could unite over a common cause: working to protect the remaining non-captive animal populations from extinction. Let’s join together the very best characteristics from both sides of the aisle. Join the mega audience of zoos and aquariums, (with an attendance greater than all professional sports combined), with the marketing, messaging and PR skills of the animal rights groups, whose ability to incite passionate action is unrivalled.

A snippet of my quite controversial post over at Blooloop.com about my naively optimistic wish of eliminating the US vs THEM mentality that has invaded every aspect of our world:

"But my real wish, my dream, is of, “what an amazing world this would be’ if we could all join forces. We could unite over a common cause: working to protect the remaining non-captive animal populations from extinction. Let’s join together the very best characteristics from both sides of the aisle. Join the mega audience of zoos and aquariums, (with an attendance greater than all professional sports combined), with the marketing, messaging and PR skills of the animal rights groups, whose ability to incite passionate action is unrivalled.

Let’s redirect our efforts for productivity, for proactivity, and stop fighting each other. We need to listen and learn; critically review our policies and procedures, create new programs, and focus. Let’s save habitats and wildlife. Because really, we’re all on this earth together, so why not be all in this together?"

8 Characteristics of Great Brand Experiences

My latest post to Blooloop.com is now live! In this article, I explore the appeal of today's competition to zoos and aquariums: sports, games, streaming services, fitness, and festivals by looking at their common attributes. By understanding what draws people in and keeps them coming back, we can apply those same attributes to our attractions' designs--and even develop non-attraction attractions (creative marketing experiences?) that may be temporary in nature, but increase revenues and drive attendance.

Check out the article here.

Zoos in a Post-Truth World

We all know about 'fake news' and we should all be aware of the growing distrust of anything big: big media, big government, big business. How does this skepticism affect the authority of zoos and aquariums as knowledgeable and reliable sources of information? How do we counter the growing culture of concern about zoo and aquarium animal care? How do we prove the validity of these institutions to exist at all when, it seems, logic and reason has all but left the building? I explore some simple ways to build and retain trust with our market and maybe even gain broader audiences in my latest Blooloop.com blog post. Read it here.

The New Zoos: Designing Spaces With Animals in Mind

I was recently interviewed for an article about the complexities of zoo design especially in relation to animals' needs. It's a great article on VetStreet.com. Check it out!

Giraffe Feeding Beneficial to Animals

Recently, I was engaged in a friendly debate about the merits (or faults) of a giraffe feeding experience. One of the issues that came up was whether or not the experience negatively affected the animals. As it turns out, a student at my alma mater, Michigan State University, was wondering the very same thing. His research, documented via poster for the AZA Conference Poster Session, indicates giraffe feeding programs act as a form of enrichment for the animals, and are therefore beneficial. His preliminary results follow:

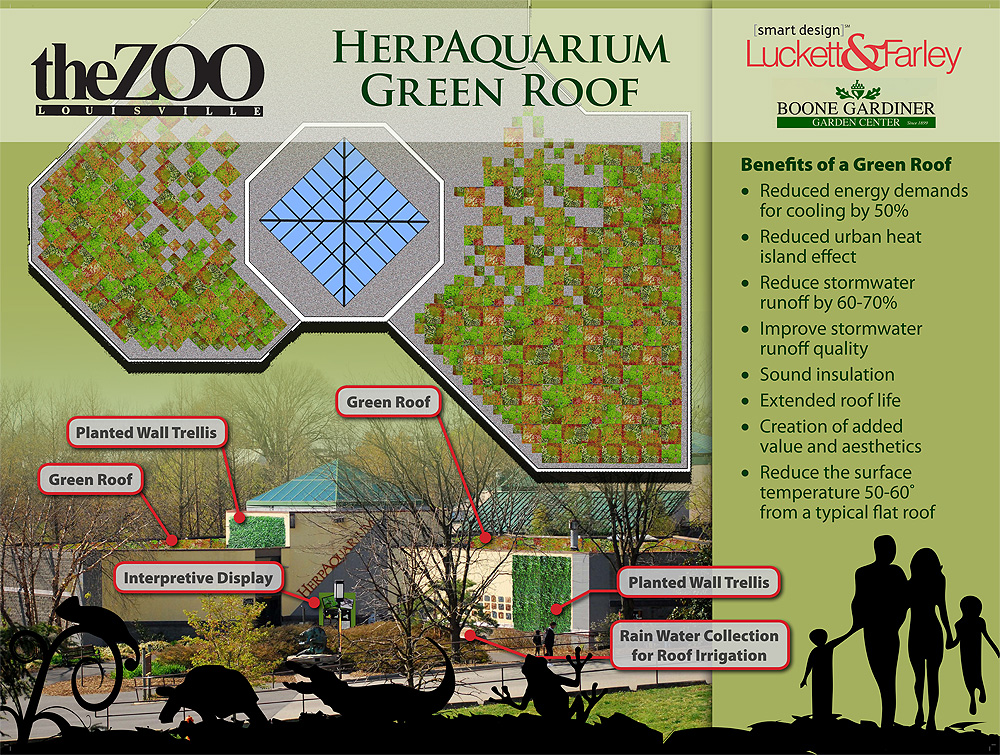

The Greening of Zoos

Recently, the PGAV Specialty Development Team has been spending a lot of time focusing on practical applications of green principles in the complex world of zoos and aquariums. (We have spent very little time looking at aquariums as the amount of energy required to run an aquarium is beyond the practical approaches we are familiar with at our basic level of understanding.) But, nonetheless, zoos are making strides in the green world. And are finally getting recognized for their efforts. In 2010, Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Gardens was named the National Energy Star Greenest Zoo in America for their work including a Platinum LEED building and the installation of solar panels over their parking lot. That same year, the Indianapolis Zoo received a Governor’s Award of Environmental Excellence for their recycling program, and was the first zoo in the nation to receive the EPA’s Green Power Leadership Award for their commitment to purchase electricity created by green means.

But, I was curious. What are most zoos doing these days to become green, or at least, to give the impression that they are ‘going green?’ And, how many of these practices are things that we as zoo designers can positively influence or encourage through design?

Last month, the Zoo Design SDT investigated those questions through a rather admittedly simple exercise: We browsed the internet to find green zoos and their practices.

Each of us collected the green practices of three zoos by searching for ‘green zoo’ on Google, then searching for all of the practices that zoo had published online. We then sorted the practices into general categories, like Sustainable Purchasing, Solar Panels, and LEED Projects.

We quickly realized that these categories fall into two overall groupings: Operational Practices and Physical Plan Components, or “Things we probably can’t affect” and “Things we definitely can affect,” respectively.

After gathering all of these practices, it is abundantly clear that although zoos are making strides to become responsible green leaders in their communities, there is a lot of room to grow. Most zoos have strong recycling and composting programs, have initiated a green purchasing program for zoo products (like compostable or corn based dining wares and recyclable content paper products), and have implemented strategies for decreasing utilities usage (like programmable thermostats and lighting on sensors). But more than that, consistent programs are scarce.

And physical plan green principles are the least implemented thus far. This indicates that although zoos have the best intentions, we have a long way to go, and as zoo designers, we are perfectly perched to help guide zoos through into the next generation of zoo design: Green zoo design.

To review realistic green options for exhibit design, re-check out my previous post "Green Design in Zoos."

How Animal Behavior Drives Zoo Design

Some designers begin with a poem. Others look at the educational message. Still others envision a place. I always start with the animal. When I start my design process with the animal, I don't literally mean that I sit down with Google (or even--do you remember this--flipping through books!) spending hours researching the animal's natural history. What I mean is that I immediately register what I know about that animal and have that inform all aspects of design. Of course, I've been doing this for a while and I have quite a bit of animal trivia logged away in my own dusty library of grey matter.

But, really, what is it that informs design? What information about an animal is truly useful in creating its surroundings? The subject of animal behavior is a nearly unending panacea of amazing stories, but determining what facts help inform design can be an overwhelming question.

To help you navigate the masses of information available about specific animals, I've condensed the vast subject of animal behavior into six basic categories relevant to zoo designers.

1. Food Acquisition: Are they carnivores, omnivores, or herbivores?

2. Social Structure: Do they live in groups, pairs, or singly?

3. Time of Activity: Are they nocturnal, diurnal, or crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk)?

4. Micro-Habitat: Do they live primarily in trees (arboreal), on land (terrestrial), in water (aquatic), or some combination of any or all of the three?

5. Personality: Are they shy, curious, skittish, indifferent, vicious?

6. Reproduction: Does their reproductive strategy require any particular element in their physical environment?

Each of the above will provide insight into the physical surroundings that will best house an animal in captivity. For example, carnivores tend to exert energy in bursts, spending the rest of the day sleeping. They also tend to prefer the high vantage points where they can scan the horizon and smell the air. Knowing this, we'd immediately suggest providing this carnivore with several high points in their exhibit, preferably where they can be in close proximity to the guest as they sleep. Jungala at Busch Gardens achieves this well with their tiger pop-up--highest point of the exhibit is actually a viewing window!

Another great example is the amazing bower bird. We could easily create just another generic aviary with a gravel floor or concrete basin. But understanding their reproductive behavior would allow us to create an environment whereby they are able to create their own habitat. {Or, more than that, we could re-create one of their creations on the guest side of things in order to illustrate their great ability.}

Beyond these basics, understanding animal behavior encourages us to strive for ever-more enriching environments. To design an enrichment device, or simply to provide a habitat that provides the most basic form of enrichment--choice, requires that you understand the natural history of an animal.

Oftentimes designers who do not have a specialization in animals, jump immediately to the guest experience; creating a place or a story for the visitor. But, we must understand that a good guest experience at a zoological park revolves around the ANIMAL, not the setting we create. People come to the park to see animals. And if the animals look unhealthy or unhappy, the most beautiful ancient Mayan ruins won't save the experience. Look to the animals first. Be inspired by their lives before creating a story, and you'll see that your final product will be by far the best experience possible for both guests and the animals living there.

Every animal has a story. Its our job to tell it.

Resources:

"Integrating Animal Behavior and Exhibit Design" by John Seidensticker and James Doherty

"Part Five: Behavior" from Wild Mammals in Captivity

Rotation Exhibits: How To Guide

The idea of rotating animals through several exhibits as a means of enrichment and variability is a relatively new one. The popularity of the idea is widespread, despite the requirements of large spaces, intensive staff involvement, and complex (or flexible) holding facilities.

Generally, we've been incorporating some sort of rotation capability in all of our exhibits for the past several years. If the staff is willing, the advantage is great: providing several smaller exhibits in which to rotate through the animals during the day provides active animals, which in turn, provides engaged guests.

Generally, we've been incorporating some sort of rotation capability in all of our exhibits for the past several years. If the staff is willing, the advantage is great: providing several smaller exhibits in which to rotate through the animals during the day provides active animals, which in turn, provides engaged guests.

The upcoming Louisville Zoo Glacier Run exhibit takes full advantage of this type of exhibitry. Despite the main exhibit area being on the small size, the bears here will have several play areas away from the main exhibit, thereby increasing the overall territory of the animals. The downside to this is casual visitors may not understand the complexity of the bears' lifestyle, and may judge the exhibit as inadequate.

However, understanding how to incorporate this important concept will enhance most zoo exhibitry, and many times, is a creative solution to a tricky problem. Read more about rotation from da man, Jon Coe, here.

Alternative Zoo Design Revolution?

For those following the conversation yesterday about the next big step in zoo design, I'm posting the article by Coe and Mendez that outlines his theory of the "Unzoo." Let me know what you think!

The Next Zoo Design Revolution?

Landscape immersion, which is a type of design intended to "immerse" the visitor in the same natural habitat as the animal, effectively began with the Woodland Park Zoo's gorilla exhibit. Created by zoo design godfathers Grant Jones and Jon Coe as a collaboration with Woodland Park then-director David Hancocks and biologist Dennis Paulson, they coined the term landscape immersion, and thus began the philosophical shift from a homocentric view of zoos to a biocentric view. We now spend massive amounts of resources re-creating "natural" places and cultural phenomena, in an effort to connect people to the earth; to inspire respect of natural places. Back in 1978, this style of design was fresh, new, innovative, revolutionary; nearly thirty years later, the style has become so a part of zoo culture that any exhibit not designed in this manner is questioned for its validity and chances of success. However, should landscape immersion continue to be our design standard? How do we push to the next step beyond landscape immersion?

True and successful landscape immersion requires designers to experience a habitat first-hand before beginning to design a re-creation of it. They research the essence of the habitat, the ecosystem structure within the habitat, and the natural ebbs and flows the habitat would undergo. The animal is an integral part of the ecosystem, not just the centerpiece of a painted scene. The visitor is whisked away to another world, drastically different from the asphalt sidewalks and ice cream shops of the zoo midway. Today's landscape immersion is, too often, not this. Today's landscape immersion usually means planting the visitor space with the same plants as seen in the animal exhibit, and using props from a culture as shade structures, means to hide back-of-house buildings, and educational interpretives. Moreover, today's visitor to a modern zoo no longer has their breath taken away by a landscape immersion exhibit; they simply expect to be immersed in an animal's habitat. The magic of landscape immersion is gone. Along with that, the opportunity to educate and inspire is waning, because, as Coe has said himself, "Only the emotional side, in the end, has the power to generate changes in behavior" (Powell, 1997). If the "oh my" moment is gone, does education stand a chance?

Landscape immersion does not generate longer experiences, as commonly believed. This can easily be shown true by simply observing visitor behavior at exhibits. After studying visitor length-of-stay time at viewing areas, little to no difference can be observed between the old, concrete moated tiger exhibit at Philadelphia Zoo and the landscape and cultural immersion tiger exhibit at Disney's Animal Kingdom. The average maximum stay time of 90 seconds has been consistently shown through observations at other exhibits as well, including the gorilla exhibit and bongo exhibit at Cincinnati Zoo, and the polar bear exhibits at Detroit Zoo and Louisville Zoo. Despite renovations and millions of dollars spent on landscape, rockwork, and interpretives, the most we can expect of our visitors is a minute and a half. Is this time shorter now than at immersion exhibits in the early 1980's? What can we do now to increase this time? Or, what can we do to get the most impact for our minute and a half?

One of the biggest complaints against landscape immersion is the difficulty, generally, in spotting and clearly seeing the animals. Therefore, proximity to animals should be a chief concern in exhibit design. Visitors want to experience something special. They want to do something no one else gets to do; something they have never done. Most importantly, in doing these things, visitors feel connected to the animals. Creating the connection should be of the utmost concern for designers and zoos.

Another component lacking in modern zoo design (not just landscape immersion specifically) is the integration of behavioral enrichment into the basic design process. Too often behavioral enrichment is an aspect of the exhibit that is not addressed by zoos to the architectural designer, even if the behavioral enrichment program is being developed concurrently. Most zoos still see the enrichment program as a separate aspect of the new exhibit to be implemented by the keepers after the exhibit is opened. Most architectural designers are ignorant to the importance of behavioral enrichment as a means not only to increase the health and welfare of the animal, but also in creating an active exhibit with active animals, which translates into longer stay times. Thus, enrichment generally is not addressed as an aspect of design, and ultimately we see beautiful new landscape immersion exhibits with large orange boomer balls and blue plastic barrels. Can these be considered cultural props? Recently, behavioral enrichment has been integrated beautifully into primate exhibits, but what about ungulates and big cats?

Connection creation and enrichment are the two most important issues that we must address in order to move beyond landscape immersion. The complexity of stepping beyond landscape immersion may seem a daunting task. However, the essence of the next successful step will be in creating "novelty"-something new or unexpected. Novelty to visitors, both within every new exhibit they encounter, as well as within the same exhibit upon repeat visits. We must create novelty to animals, both in new enrichment devices and methods, as well as within their own habitats. We need to make adaptable habitats that can be changed on a daily, weekly, monthly or seasonal basis. We need to make experiences for the visitor and animal that they can share, becoming intuitively novel, since every person or animal will react slightly different in new situations. Thus, our new exhibits will stay new, increasing visitor repeat attendance, and discouraging cookie cutter exhibit design.

But how do we begin to do this? In addressing the issues of connection creation and incorporation of enrichment into design, the first and most critical step will be to develop stronger relationships between architectural designers and zoo staff. Designers need to be educated by the keepers on animals' behaviors, both in the wild and in captivity, as well as on methods of behavioral enrichment. Designers should spend a day or two working side-by-side with the keepers as "keepers for a day." This will help designers to not only understand the needs of the keepers in their daily work routines, but also to help create bonds between designers and the animals whose homes they are creating. The zoo staff has a passion for animals that most architectural designers are lacking. This passion needs to be shared and experienced by the designers.

In "novelty-based" design, zoos and designers need to work together to develop new methods of enrichment and test them before integrating them into design. Design schedules and budgets should include a phase for enrichment development and testing, wherein the designers work with the keepers to create prototypes to be tested with the animals. If the zoo is designing exhibits for animals they currently do not have in collection, partnerships should be developed to test enrichment devices at other zoos with those animals. These findings should be recorded scientifically and published for the entire zoo community to share. If the zoo uses training as enrichment, the designers need to experience training sessions and clearly understand the need and utility of the training. Keepers and designers should be discussing how all of these methods can be displayed on exhibit.

Specific enrichment goals need to be addressed at design kick-off meetings, making numerical goals for incorporating enrichment devices and creating new methods. Enrichment must be seen as a philosophical aspect of design, incorporated into the master planning process, because if animals are active and happy, visitors will become more engaged. Enrichment must be planned not only for the opening day of the exhibit, but for the future of the exhibit as well. Animals become acclimated to enrichment devices and stop using them. We must plan for this, developing phasing plans for enrichment, and flexibility of the exhibit design for novelty of the environment. Most importantly, after the construction is complete, studies must be conducted to determine the successes and failures of enrichment techniques. These results should be shared with the zoo community, and especially, the designers.

Secondly, the "novelty-based" design process must become "connection-centered," not visitor-centered or animal-centered. Connections are created both by proximity and by experience. Landscape immersion began to explore this idea by attempting to have visitors and animals in the same habitat, thus experiencing the same things. However, in landscape immersion, we don't experience the same things at all. As visitors, we have a choice to move into a different area, to eat ice cream or hot dogs, to sit and watch the gorillas or to go see the penguins. We don't swim in the same water as the polar bears and we don't get to swing around on ropes like orangutans. What if we started creating these shared experiences? Can we make environments for animals and visitors that are truly similar? What if the actions of a visitor change the environment for the animal? What if the actions of an animal change the environment for the visitor? No longer would we be bound by the idea that the habitat must look like the animals' wild habitat. We could make it look like any thing, any place, any time, as long as the visitor and animal are engaged and ultimately, connected.

We have already seen a movement starting to push beyond landscape immersion, and, in some instances, toward "novelty-based" design. Several new exhibits, including the St. Louis Zoo ‘Penguin & Puffin Coast' exhibit and the San Francisco Zoo's ‘Lipman Family Lemur Forest', utilize natural habitat but also incorporate distinctly non-immersive elements, and are exceedingly successful. These exhibits focus on getting the visitor close to the animals (connection-centered) and being surrounded by active animals (behavioral understanding and enrichment incorporation). This experience, which will be different and therefore novel upon each visit, makes these exhibits extremely emotional and therefore memorable to visitors, and begins to create a connection. These exhibits are a step in the right direction toward "novelty-based" design. Using this type of design, we can move to the next incremental step in the evolution of landscape immersion, keeping the "oh my!" moment, and continuing to educate and inspire our zoo visitors.

A Quick Lesson in Zoo Design History

Over time, zoos' physical forms have been a direct reflection of our society's values and understanding of science. It is important to understand where we've been in order to move forward, and its is also important for visitors to the older zoos to understand why certain buildings and exhibits are the way they are (as we know, zoos usually do not have an abundance of money, and struggle to keep their physical state up with the trends). Zoos, in the form we know them now, have been in existence since the mid-18th century. Prior to this, private collections existed throughout the world as far back, it is believed, to Mesopotamian times. Romans kept animals, of course, for sport, but would display the animals in a zoo-like manner, prior to their being released to their deaths in the Coliseum. But we'll focus on the mid-19th century forward.

We can easily divide the eras in zoo design into three general categories:

Zoos as Jails (mid 19th to late 19th century)

Zoos as Art Galleries OR the Modernist Movement (early to mid 20th century)

Zoos as Conservation and Education Facilities

Zoos as Jails

This was the Age of Enlightenment and the Romantic Age, where beauty was of the upmost value and our understanding of the natural world was blossoming into a science. Hard science in this time was all about classification and comparison. Linneaus and Darwin were the scientific stars. The earliest official zoos began during this period, with the London Zoo in 1828 and Philadelphia Zoo in 1874. The early zoos were based on the mission of science for science's sake, but also were places for socializing.

As such, a balance between beauty and classification was struck. The zoos of this time were laid out by taxonomic families, and the term "House" came into being, as in Cat House, Bird House, etc. The architectural style was over the top beautiful. Highly ornate bird cages and buildings themed in the most dramatic fashion were everywhere. But, cages were small, animals were short lived, and people enjoyed the animals as beautiful objects rather than living beings.

Zoos as Art Galleries OR the Modernist Movement

During this time, the world was experiencing several wars. The study of nature became much less important, but Romanticism still existed. Science progressed into problem solving, and medical advances were abundant. Vaccinations became prevalent and the idea of killing germs to increase health and extend life expectancy came into being.

During this time, zoos held a similar value as art galleries, and the exhibits became mini-paintings and sculptures. In the Romantic movement, a proper landscape exists with a foreground, mid-ground, and background. Carl Hagenbeck became the first-ever to apply this theory to zoo design resulting in the birth of the barless (or 'moated') exhibit. His motivation was more about creating a living Romantic landscape, like the famous painters of his time, than to recreate nature for moral sensitivities. This style started to catch on in zoos, but generally became popular much later.

At the same time, the modernist movement was catching fire. Modernism requires that form follow function. This belief along with the advances in medicine and desire for sterilization, created zoo exhibits that were easily hosed down and cleaned regularly. This meant concrete everywhere. Additionally, the Modernist Art scene infiltrated zoo design, and the hard, simple lines for which modernist style is famous, reigned supreme. The result was exhibits that look more like sculpture than habitat.

With both the Romanticism and Modernist styles abounding in this time period, zoo design was more about creating an art gallery than a responsible home for animals. Interestingly, due to the increased attention to health, captive animals' life expectancies did increase almost to today's levels. The only thing missing was attention to the animals' mental health.

Zoos as Conservation and Education Facilities

Since the mid-20th century, our society has developed a strong sense of environmental awareness and human rights ethics, which eventually gave way to animal rights as well. In 1950, Hediger wrote "Wild Animals in Captivity" which opened people's eyes to the idea of husbandry practices and exhibit design based on an animal's natural history. What a novel approach! With the advances in healthcare (which overlaps into this era), animals in captivity began to be treated for physical as well as mental health.

During the 1970s, a group of folks at the Woodland Park Zoo (including two young designers from Jones and Jones Architects) decided to resurrect Hagenbeck's ideas from long ago--and to advance them.

Instead of creating a living painting, they wanted to put the visitor into the habitat...Immerse them in the painting. And, instead of creating a visually exciting statement only, they decided to re-create the habitat in the which the animal was naturally seen. All of these things were incorporated into the gorilla exhibit at Woodland Park Zoo, and, thus, landscape immersion was born.

Since then, the idea of landscape immersion has caught on like wildfire, and today, is the standard of responsible zoo design. Understanding the past, I have to wonder where we are headed next...A topic for future discussion.

The Future of Science Based Institutions

The question of co-evolution amongst zoos, aquaria, and science museums has been a lingering muse for decades now. Back in 1986, Jon Coe cleverly equated the historical relationships to convergent evolution, and through his paper, which was more history lesson than predictor of the future, compared their similarities through time. Ultimately, he suggests "an awareness of others and ourselves, together with a willingness to communicate, can lead us further into an exciting co-evolution of zoo, aquariums and natural history museums." I'd like to take it a step further.

I often wonder why we separate all of our science institutions, dividing the natural world into equal, but succinct pieces: land animal (zoos), plant (botanical gardens), aquatic animal (aquaria), and the sciences (natural history museums and science centers). Of course, overlap occurs; zoos have fish and aquatic mammals, botanical gardens have butterfly houses, science museums have dioramas of the natural history of living creatures. Additionally, the method of teaching the general sciences varies greatly from conservative natural history museum approaches to more "fun" and interactive science centers.

As Coe mentioned, the teaming up of these institutions would be a powerful force. However, if, going beyond what Coe suggested, we created one institution that presented all of these disciplines, we'd be teaching holistically, presenting a unified view of the natural world that so many children and adults rarely get the chance to see.

The world has changed dramatically since the inception of these learning institutions. Most zoos and natural history museums began at the turn of the 19th century, when for the good majority of people, we still lived in a mostly untouched rurality. These people grew up with nature, lived in nature, or could easily visit nature, and learning about the natural world was most easily understood by the breaking down of components.

Today, however, most people live in cities or suburbs. Any nature we experience regularly is man-made or man-influenced, and certainly does not contain a wide variety of species or habitats. Learning about nature now becomes easier through an immersive, holistic approach. Add in society's constant bombardment with story driven entertainment and eye-candy, and learning almost requires the same treatment. Or so I postulate.

The Museum of Life and Science in Durham, North Carolina has already come to the same conclusion. Currently, they house live animals, present botanical displays, a natural wetland trail, and incorporate hands-on science center activities throughout. This is not enough for them, however.

We envision a one-of-a-kind place, a science park, offering extraordinary experiences indoors, outdoors, and virtual where children and adults learn through the pursuit of their own interests and curiosity. We will be recognized as the leader in public engagement with science in the Triangle region and as a model for science museums across the nation.

Will this be the future of science institutions? A one-stop shop, so to speak, for education and entertainment about the natural world? All things are intertwined; nature is a web of life. Why not present it that way?

Read the follow-up to this post: 'MULTI-DISCIPLINARY INTEGRATION...A MOUTHFUL OF FUN.'

Enrichment Based Design, Revisited

Over ten years ago, Jon Coe wrote a paper outlining the upcoming breakthroughs in exhibit design, using enrichment based (or as he says, activity-based) design. These exhibits have now been opened and are successful. However, ten years from the original date of the paper, designers still have not fully embraced the design concept. Incorporating enrichment devices into an exhibit is one thing; to fully base design on enrichment or activity, is an entirely different animal. As Coe points out, however, design is not fully the designers' decision. A new animal habitat has many stakeholders, and even if the designer supports the idea of basing design on enrichment, the entire team of administrators, keepers, curators, and Board of Directors, not to mention all members of the design team, must also agree.

In many cases, the resources (of time, money, and/or space) just aren't there. Many times, the decision comes down to making an immersive environment or making an enriching environment. Unfortunately, many folks in the industry still hold onto the idea that an immersive environment equals animal health and activity, or at least, equal visitor satisfaction. However, active animals are much more powerful than a pretty environment, and we must work on our clients to understand this.

Studying Visitor Behavior

I've written in the previous posts about my experience studying visitor behavior at zoos. Well, I've briefly mentioned it, at least. Although many zoos throughout the U.S. are studying visitor behavior, it is a rare occasion for designers to get the chance to get the first-hand experience of studying how visitors use their designs. I highly recommend doing some informal visitor studies at exhibits you've designed as well as at those you have not. From my past visitor studies, I've learned two consistent lessons:

1. Visitors stay at each viewing station less than 90 seconds. No matter what species is displayed, or how well they are displayed. The only exception is when the animal is extremely active. For example, studying visitors at Disney's Animal Kingdom's beautiful tiger exhibit, I noticed a major spike in visitor length of stay, from the average 90 seconds to upwards of 9 minutes when the tigers had, serendipitously, spotted a rabbit in their enclosure and subsequently went into hunting mode. The experience was mesmerizing, and everyone was swept up into the excitement. This makes me wonder if live feedings shouldn't be more acceptable...but that's another story.

2. Less than 2% of visitors fully read signage. Fully interactive interpretives may be a different story. None of the exhibits I have studied had any of these more modern interpretives.

Researchers at Chicago's Lincoln Park Zoo studied visitor behavior following the opening of their recently opened Regenstein Center for African Apes. The article written outlining their experience supports only one of my lessons...No one reads signs. However, their visitor stay time far exceeded anything I've encountered (although they measured their length of stay differently, by measuring the full exhibit stay time rather than per viewing window).

That researcher in the ape house? She was studying you.

By James Janega

Tribune staff reporter

April 26, 2007, 10:57 PM CDT

The animal behaviorists at Lincoln Park Zoo have given simple tools to gorillas and taught chimpanzees to navigate computer touch screens, but their latest experiment involved a primate so intelligent and cagey, it was going to take work to outsmart it.

The subject was people and to measure their behavior at the zoo's ape sanctuary without them catching on, a 24-year-old zoo office worker with girl-next-door looks would have to slip on quieter shoes, wear muted colors and follow people in secret by watching their reflections on glass.

Starting last spring, conservation assistant Katie Gillespie spent a year clocking visitors' stays in the Regenstein Center for African Apes, noting where people loiter and what they look at.

With her boss, Steve Ross, she frowned when people ignored interpretive signs and took smug comfort when subjects were captivated by apes. For months, she and Ross hoarded statistical glimpses into how humans prefer to learn about chimpanzees and gorillas.

It was all very scientific, not to mention fun and kind of sneaky.

In the course of 476 observation sessions over 12 months, Gillespie and Ross learned that everybody likes watching apes and nobody likes reading signs. They found people love to pose with ape sculptures, and that parents all too often make up answers for their children.

And they proved the best way to fool people is to let them fool themselves.

"I've had people ask me what I'm doing," Gillespie said. "I tell them I'm taking behavioral data. Then they ask me questions about the animals."

Gillespie, who has a bachelor's degree from the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point, trained in natural resource management and has a day job as exotic as her office cubicle.

As for zoo experience, she made signs for a raptor walk at the Marshfield Zoo near Wausau. Her real job at Lincoln Park Zoo involves administrative tasks at an office a few minutes away from the ape building.

But on Feb. 21 last year, she climbed into an unlit, concrete mezzanine at the Regenstein Center, looked out windows tailored for watching animals, and listened as Ross told how to follow people without them knowing.

It was a slow morning in the ape center, a tough time to avoid notice. But there are tricks of the trade, Ross reassured her.

Downstairs, other conservation assistants were using Palm Pilots to study apes. Hold one, and people will assume you're watching chimps, he said. Get ahead of people and let them pass you. Use reflections and peripheral vision.

He used the word "spy." Gillespie got the job after biologists told Ross they'd rather watch apes, not people.

Ross had done this before, in 2000, but inside the old, round, dark Great Ape House, a cinch compared with the Regenstein Center's bright, open floor plan. This new place, built in 2004, upped the ante. You could get caught.

"I've had an awful time getting people to do this," Ross told her.

Gillespie stuffed printed explanations of the study in her pocket that included Ross' phone number, to hand out in case she was confronted. In those first days, she wondered if it was going to work.

"It's almost impossible," she exclaimed early on. As a practice subject approached the entrance, she hurried down the metal stairs to the floor below, her high-heeled pumps clanging on each step. The ringing subsided just as the subject opened the door below the mezzanine.

"We gotta get you some sneakers," Ross told her later.

By May and June, when school groups crowded the floor so thoroughly it was hard to move, Gillespie was an expert. She followed kids in camp groups in July, vacationers in August and September, and aborted an observation only once-when a young couple started making out.

It turned out the challenge wasn't getting caught, she found. It was battling exasperation. People complained when the apes sat around, in the middle of rest cycles clearly defined on nearby signs. Parents made up answers to kids' questions. People made mistakes, and no one corrected them.

"You hear people asking questions that are written all over every sign everywhere," Gillespie said of those moments. "But you can't influence them."

So she just observed-always the fifth person to enter after the last subject left. The sessions were always anonymous. Regulars were ignored.

Her shortest follow came on a sunny Sunday afternoon in June: a girl in an organized group who stayed 2.3 minutes while a heavy crowd shoved through the air-conditioned building. The longest visit was in December, a woman with children who relaxed for 116 minutes. January brought visitors in a steady, unhurried rhythm. Often, the subjects stood at Gillespie's elbow without knowing.

One was the man in the blue coat. At midday on Jan. 24, 2007, Gillespie, wearing moccasins, padded down the stairs from her mezzanine perch to beat him to the chimp enclosure.

Behind her, the man watched JoJo's gorilla troop, then breezed past an interpretive display to study Hank and his group of chimps, where he planted himself in front of Gillespie to do it.

She wore a zoo badge and appeared to watch the animals. Every 15 seconds, her Palm Pilot chirped a reminder to note the man's behavior: "Locomote," "Watch Chimps," "Photo Chimp."

The terminology was borrowed from animal behaviorists, and the man in the blue coat had no idea the soft beeping was for him.

Over 29 minutes, Gillespie took two pages of behavioral notes. The man watched both gorilla troops, talked to docents, took more pictures and left. The list recorded only movement, location and activity.

But on the floor it looked like more. It seemed like deep fascination.

A full analysis is months away, but some things are clear.

Watching apes was the most popular behavior, and visitors lingered more in the airy naturalistic environment than in the previous concrete-and-steel building.

The most popular exhibit elements were life-size hands and busts of various apes, which people touched and photographed regularly. The average visit was 15.5 minutes.

But many zoo interpretive standbys fell flat. Just about everyone ignored a looping video describing behavioral research on apes at the adjoining Lester E. Fisher Center. They likewise ignored graphics beside actual apes that described a "day in the life" . . . of apes.

People learned by watching apes that acted as they do in the wild.

It was an epiphany for Gillespie that came on one of her last observations. In February, a young mother brought her 1-year-old daughter to the chimp enclosure where Kipper, a young male, showed off for the girl through the glass. The mother and daughter were delighted by the connection.

"You knew that this was such a special moment that they would remember," Gillespie said. "And maybe that would be more impactful. Even though they weren't reading signs."

jjanega@tribune.com Copyright © 2007, Chicago Tribune

I fully believe every time a new exhibit is proposed, designers should spend at least one day watching how visitors use the old exhibit, and / or similar exhibits (to that proposed) at other zoos. Additionally, we need to instate an industry standard of post-opening visitor behavior research. Most institutions do some amount of study post-opening, but that information is rarely passed onto the designers. Designers need to be proactive and spend some time at their creations, truly critiquing the successes and failures. Only then will we be truly able to truly be experts.

Natural Enrichment Ideas for Exhibit Design

We've all been witness to, and some of us may be to blame for, the red boomer balls in tiger exhibits or the blue barrels in the polar bears habitat. I've heard guests laugh about beer kegs in the bear exhibits, implying in some manner that the bear's an alcoholic. Positively enjoyable for the guests and the bear, but still a problem as they bring a wholly artificial element into an otherwise "natural" setting.

In an effort to curb these disruptions in our suspension of disbelief in an immersive zoo exhibit (in other words, in order for us to get rid of any sign that we are, in fact, in a zoo, and not in Borneo or Alaska), we need to start planning the enrichment as a part of the exhibit design process with the keepers.

Jon Coe wrote a nicely illustrated paper for the Australasian Regional Association of Zoological Parks and Aquaria conference back in 2006. Within this paper not only does he clearly outline several concepts for enrichment devices within exhibits, but also lays out some general guidelines. Take a look!