As a designer dedicated to the long-term planning of zoos and aquariums, I’ve had to explain the process of master planning many times, and although every zoo and aquarium is different, the best master plans (i.e. those which have been implemented) always follow a similar structure. In this post, we address the most commonly asked questions to help you understand what master planning is, when is the right time to start, and who should be involved.

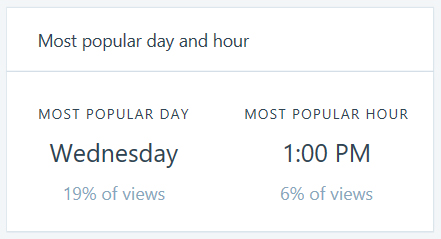

Happy Anniversary! 10 Years of DesigningZoos.com

Can you believe this summer marks ten years of my little corner of the internet talking about design and the future of zoos and aquariums? Although my posting has become more infrequent as my professional life has evolved, you--my supportive and sometimes thoughtfully critical reader--remain constant. I owe you a huge Thank You for reading my ramblings, and contributing your thoughts. For funsies, I thought we'd review a few of the highlights from the past 10 years and over 200 posts!

Top Ten All-Time-Most-Popular Posts (by visits)

10. "Visitors: An Overlooked Species at the Zoo" (2013) by guest blogger and colleague, Eileen (Ostermeier) Hill. Discusses the critical importance of visitor studies at zoos, some hurdles to studies, and the role of designers relative to visitor studies.

9. "The Future of Zoos: Blurring the Boundaries" (2014) a second entry by guest blogger and obviously brilliant colleague, Eileen Hill. Powerpoint presentation with script about trends in zoos today and how they may play out into zoos of the future. Eileen proposes zoos of the future will by hybrids of multiple science based institutions.

8. "St. Louis Zoo's SEA LION SOUND" (2012). Showcasing the then-new exhibit at the Zoo including fly-thru video, photos of new exhibit, and interview with one of the architects from PGAV Destinations who helped bring the design into reality.

7. "SAFARI AFRICA! Revealed at Columbus Zoo" (2012). Announcement of the ground-breaking of the eventual AZA Top Honors in Design award-winning Heart of Africa (renamed). Includes renderings and site plan.

6. "Underdogs: The Appeal of the Small Zoo" (2013). Exploration of what makes small zoos so appealing to visitors, and meaningful to work for as a designer. Features Binder Park Zoo, Central Florida Zoo, and Big Bear Alpine Zoo.

5. "In Marius' Honor" (2014) by guest blogger and now Project Manager at the esteemed Monterey Bay Aquarium, Trisha Crowe. Trisha explores her emotional reaction to the Copenhagen Zoo's disposal of Marius the giraffe, and implores readers to support zoos, no matter your stance on animal rights.

4. "Small and Sad: Dubai Zoo's Relocation on Hold Again" (2009). Occurred to me today, should have been title "Small and SAND", but the sad state of the old zoo is what made this post so popular. Includes design plans and renderings--which I am sure are woefully out of date. Anyone have any updates??

3. "How to Become a Zoo Designer" (2014). After about 25,000 emails from aspiring zoo designers asking similar questions, I just went ahead and wrote it up to shortcut a step... Still, feel free to email me--I always write back. Let's be pen pals!

2. "The Next Zoo Design Revolution" (2008). One of my very first posts, which explains the popularity. Some say naïve, some say gutsy look at incremental revolution in zoos. The future of zoos has been examined at least 300 times since this one, but in re-reading, I see some kernels of accuracy. Expect an update soon...

And in the #1 spot....

1. "A Quick Lesson in Zoo Design History" (2008). Perhaps my second post ever, which again explains it's number 1 spot. A not-as-advertised look at zoo design history which, I have a feeling, has been referenced by many of the 25,000 students (above) in their zoo projects. Holla at me if you cited me!

Top Ten Recommended Reads for Zoo Designers (aside from those above)

10. "To Safari or Night Safari" (2008). I'm a sucker for the title. But this post examines the very slow to catch on trend of after-hours programming or extended zoo hours as a feasible method to increase attendance. Post-posting amendment: in particular, this is a great strategy for targeting adults without kids.

9. "Does Winter Have to be a Dead Zone at the Zoo?" (2013). I cheated a little on this one. I didn't actually post to DZ.com, but to my blog at Blooloop.com where many of my more recent posts have been landing. This one discusses another strategy to increase attendance by targeting the most difficult time of year for temperate zoos: winter.

8. "Zoo Exhibits in Three Acts" (2011). Storytelling in zoo exhibits, told through, what else?: a story.

7. "8 Characteristics of Brand Experience" (2018). A new one! Understanding what makes strong brands so very strong is important and applicable to new attractions at zoos and aquariums. Examined through the lens of non-zoo brands, like my fav: OrangeTheory.

6. "Interactivity and Zoos" (2013). Examining the different modes of interactivity that are available in zoos, and how they can be applied to experience. A good primer.

5. "How Animal Behavior Drives Zoo Design" (2011). Starting with animals in design can be overwhelming. What information is pertinent to a designer, and what is just interesting to know. Another good primer for learning the basics of zoo design.

4. "Chasing Big Cats: Snow Leopards and Perseverance" (2017). Being a good designer is about so much more than just having cool ideas and being able to communicate them well. Learn the qualities intangible qualities that make good designers, GREAT. Don't be afraid...hint, hint.

3. "Making Responsible Tacos: Conservation Brand Perception at Zoos and Aquariums" (2015). Adapted from a talk I gave, I examine how aspirational brand should translate to experience in zoos and aquariums using the popular taco analogy. Yum. Tacos.

2. "Five Zoo Innovations that have been around for Decades"Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5 (2014). Again, pulled from Blooloop. A series of 5 posts examining design elements and characteristics that American zoos have been implementing for decades. This series was an angry reaction to the 'revolutionary' design of metal pods floating through a zoo in Europe. A woman scorned...publishes 5 posts to prove how you don't know anything about innovation. Ha!

1. "Zoos in a Post Truth World" (2017). What every zoo and aquarium advocate needs to consider in this continued atmosphere of skepticism, critique, and distrust. As a zoo designer, you must be aware of changing perceptions and the power we have to shape them.

Top Ten Things I Learned in the Last Ten Years (Blogging or Otherwise...)

10. I'm not shy; I'm introverted

9. How to poop in a hole while wearing 3 three layers of snow pants

9a. Always pack enough Pepto tabs (at least 2 per day while away)

8. I'm not good at social media (see: 10 years of blogging and 600 Twitter followers, probably mostly for cat pics)

7. And speaking of cats, the rubbery buttons of a TV's remote control makes said remote an easy tool to remove cat hair from sofas and pants

6. I sleep better when flying in Business Class

5. Always pay the extra money to hire movers to load and unload that U-Haul

4. Writing isn't hard. Just start typing and...

3. Confidence

2. I lose all 'adultness' around ice cream and baby animals

1. Zoo and aquarium people are really the best people in the world.

Here's to many more decades of Zoo & Aquarium design!

With love and respect--

Your friend, Stacey

How to Become a Zoo Designer

Each week, I receive at least one email from an enthusiastic young soul asking for advice on how to become a zoo designer. Many requests are from college students, already several years into design school. Others are from enterprising high schoolers (and a junior high schooler or two) planning their futures. I've even corresponded with several mid-career adults, looking for guidance on how to change career paths. Every one of them (and, I assume, you, too!) are passionate about animals and seek to share that passion with zoo guests--to help them create connections to wildlife and become advocates for our natural resources. That's very admirable. That's where I started (and what keeps me energized), too.

But, let's talk some realities. As a zoo (and / or aquarium) designer, you will likely work for a private design firm, not a zoo. Zoos these days are starting to understand the value of on-staff designers, but the reality is, very few zoos actually have them; and more often than not, they do very little actual design work, or are relegated to small projects such as signage, snack stands, or demonstration gardens, leaving major capital projects to licensed architectural firms with greater resources. These zoo positions are usually most valuable as client representatives during the design and construction phases, acting as go-betweens (and sometimes decision-makers) for the zoo administration when communicating to designers and contractors. I do believe we will see an increase in these types of positions becoming available, though, as institutions realize the value of having staff that truly understand and are highly literate in design and construction--they can provide great insight to their consultants about the zoo itself, local regulations, and increase the efficiency of communication between consultants and staff, not to mention the fact that they understand drawings and help prevent issues down the line thus ultimately saving the zoo money.

So, let's say you're ready to get a job with a firm. Where do you start? Within the U.S., three major firms specialize in zoo and aquarium design (depending on how you define 'major'), and are generally the three competing for the major projects: Portico Group is in Seattle; PGAV Destinations is in St. Louis; CLR is in Philadelphia. Beyond these three, there are about 10+ small and medium firms, ranging from <5 staff to about 30 staff, located around the country that have completed zoo / aquarium design work, or specifically specialize in such. Seattle is a hot bed of activity due to "patient zero" Jones & Jones, from which most, but not all, firms that specialize in zoo design spawned. Wichita, New Orleans, and Boston are home to several others. If you decide you want to be a zoo or aquarium designer, you will likely live in one of these cities. I hope that's okay.

You've gotten a job! Congratulations! You've moved in, you're ready to go. Now what's the day to day for a zoo designer? Likely the first few years will be painful. Trust me. It's not what you expect. You'll have long hours (50-60+ hour weeks regularly) staring into the abyss of the computer, drawing things that someone else designed. Figuring out the details like the hinge on a gate or how to downspout a thematic wall. You likely will not do site visits or even be able to meet the clients for several years, until you've proven your worth. You may be shuffled from one project to the next without seeing a project from start to finish, often juggling multiple projects at once. But, it does get better, although not much more glamorous! When you do finally reach the point in your career when you get to visit the zoo you're working singularly for, you generally only get to see the inside of a conference room on a quick one or two day trip--where you'll spend the evening working in your hotel room on drawings that you didn't get to complete because you spent the whole day inside that conference room.

Still interested? Yes? Okay--let's get to what you really want to know: How do you become a zoo designer?

I wish there was a magic answer to this. There is no school of zoo design. No specific university, no highly specialized curriculum. Right now, if you want to become a zoo designer, you have to do it of your own accord. Most of today's successful zoo and aquarium designers fell into their jobs. They may have done a college project or volunteered at their local zoo, but the vast majority became zoo designers by dumb luck. They were architects or landscape architects that happened to work at a firm that happened to get a zoo project, and over time, one project became many. Before they knew it, they were experts. But, the fact that I get so many inquiries is telling me this is slowly changing. As zoos evolve, and exhibits become more engaging, young people are realizing the potential for design careers focused entirely on zoos and aquariums (museums and theme parks, too!). This will lead to more and more students with specialized experiences and focused educations. So how will you stand out??

Here are the basics I recommend:

Two degrees: Architecture or Landscape Architecture AND Zoology / Biology / Animal Sciences. It does not matter which design field you choose. The majority of the early design firms specializing in zoo design were traditionally landscape architects. That has changed. Architecture and landscape architecture are inextricably integrated when it comes to zoo design. Of course, if you are more inclined to design for aquariums, choose architecture. But if you want to design only for zoos or for both zoos and aquariums, go with what is more appealing to you. Do you like to design structures? Or are outdoor environments more appealing to you? Go with what will be most interesting to you. As for the science degree, this is not required, but is very appealing to employers. This will set you apart from other design-only students. You could also just get a minor, but doing so will be very challenging, as zoology is a highly rigorous degree while design school is extremely time-consuming. It is possible, but it will not be fun.

Focus every project where you have a choice of topic on zoos or aquariums. Believe me, it will be a challenge. You will get a lot of push-back from design profs wanting to encourage you to expand and explore. Go ahead, but if you truly believe you want to design zoos, you'll want every opportunity possible to explore this complex field.

Get an internship at a zoo / aquarium. Doing anything. You don't have to have a design internship. Repeat. You do not need a design internship at a zoo. You do need behind-the-scenes experience. Do an animal care internship. Do a marketing internship. Do whatever kind of internship you can get. You will need to understand every aspect of zoos in order to design effectively for them.

Get an internship at a ZOO / AQUARIUM design firm. Do not just get an internship at the local architecture firm near your university. This is a chance to see how zoo design really works, and get your foot in the door to one of the very few specialist firms in the country. While you are there, work hard. Ask lots of questions. Share your passion. We remember it when it comes time for you to send in your resume after all those years of school.

Research and network on your own. Visit zoos and aquariums as often as possible, attend AZA conferences, visit zoo design firms, get to know designers, get to know your local zoo. Basically, ask loads of questions, read as much on the topic as possible, get tours and behind the scenes as often as possible. Learning on this topic is not going to happen in school. You have to spend your own personal time researching and educating yourself.

One of the wonderful things about the zoo and aquarium industry is that most people involved are kind and willing to help, if you ask. Zoo and aquarium personnel are in it for

the love of animals, and usually are more than happy to answer questions or direct you to someone who can. I had a lot of great people help me get to where I am today, and hopefully, I can repay their kindness by helping others on their own journey. As always, if you have any questions or need advice, just ask.

If you'd like another zoo designer's opinion, check out Jon Coe's paper on how to become a zoo designer. There is definitely much overlap!

Good luck!!

Why Master Plan?

A few months ago, I visited with a potential client--who will remain unnamed-- dealing with a complicated case of left-overs. An older institution with aging and non-immersive exhibits, a disconnected and fragmented campus, and plans in the works for a sister institution. As we toured the facilities, the director, aware of experiential and logistical issues of his multi-faceted campus, asked how I could help with one specific exhibit. I smiled and indulged him in some top-of-the-head design suggestions about visibility and theming, but ended by asking, “And what are your plans for this space?” (indicating the mostly unused plaza surrounding the exhibit). “Well, we’re not sure. We want to change it all. Eventually.”

I dropped my notebook to the floor and screamed, “Stop! Don’t touch this exhibit until you develop a master plan!” I didn’t really do that. But I wanted to.

What I did do was explain the importance of master planning. Master plans are essential to the long-term success of zoos and aquariums. They are tools for exploring and pinpointing issues. They are compasses to keep your staff on track. They are road maps for the future.

But why, you ask. Why do we master plan?

To answer the why, let’s look at the how. Generally, master plans are led and completed by zoo designers, and should include three parts: Analysis, Product Development and Implementation Planning. Each phase sets the stage for the next.

In Analysis, we look at as many aspects of the park as possible, from your market and penetration to building condition. We pour over visitor surveys, attendance and revenue records. We inspect each exhibit and every building. We talk to staff from maintenance to keepers to administrators. We gather and analyze, zeroing in on things that you’re doing well and things that are issues. At the end of Analysis, we create a set of overriding Goals and Strategies for the extent of the master plan.

The Goals are big. Increase attendance. Become world leaders in conservation. Educate our guests. The Strategies are much more specific—and in direct response to the Analysis.

For example, if our goal is to create a financially sustainable organization, some strategies may include adding a new dining facility, increasing appeal of special events rental facilities, or creating budget-friendly new attractions.

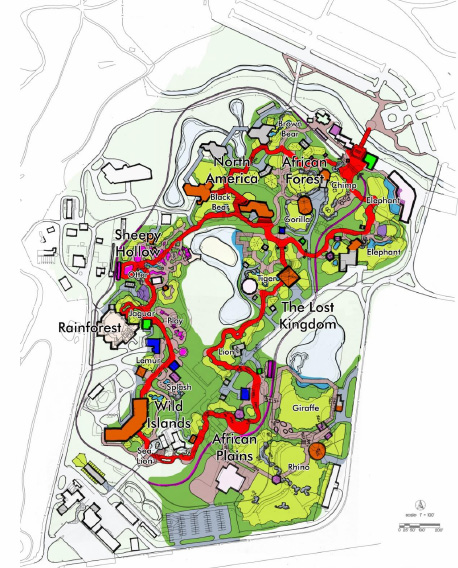

These Goals and Strategies inform and guide the Product Development process; they pinpoint specific tasks to be achieved, specific projects to be created. And in the Product Development stage, we delve into these projects. We brainstorm and explore multiple options for projects—creating many more ideas than what we could feasibly achieve in the master plan period. With these options in hand, we systematically evaluate each through the filter of the master plan goals—which often includes market testing. At the end of the Product Development phase, we’ll have a list of selected projects with conceptual storylines, plans, sketches, imagery and rough estimates.

With these projects defined, we finish the master plan by completing an Implementation plan. This phase allows us to understand ‘how’ to get these projects instated. We create a phasing plan—when will each project be rolled out?—and a funding plan—how much capital will the zoo need to raise by what dates? Finally, we create illustrative site plans defining what the zoo will look like at determined intervals (ie every 1, 3, or 5 years).

At the end, the zoo will walk away with a comprehensive plan to achieve specific goals over a set timeline. Generally, master plans plan 10-15 years out. Of course, things come up and even the best laid plans get waylaid. These surprises are exactly why master plans are so important. Because we spent so much time creating the guiding Goals and Strategies, any new issue that comes up should be tackled through the same lenses as the planned projects. Of course, Goals and Strategies may be adjusted over the years, but if the zoo finds their strategic outlook has changed dramatically from the master plan…it’s time to master plan again!

“The Master Plan gave us direction to accomplish these goals and puts us on the path to creating a more enjoyable, interactive and rich experience for the future,” said Stuart Strahl, director of Brookfield Zoo.

Finally, master plans are critical for zoos to move forward—logistically. Through a master plan, zoos have specific projects to show off, to fundraise for. The master plan provides essential visual and verbal descriptions that get the market excited and motivated to give. Not only that, the master plan is a concise definition of who the zoo is (brand today), and where they want to go (brand tomorrow). It’s a great handbook for employees, and a wonderful platform for marketing.

If your zoo doesn't have a master plan, or its master plan is out of date, the best time to start a new one is right now.

Green Design in Zoos

Back in October 2010, I was honored to be a part of the AZFA (American Zoo Facilities Association) National Conference in St. Louis, MO. In the shadow of my green genius partner, Mariusz Bleszynski (AIA, LEED AP), we presented a talk about the real nuts and bolts of green design in a zoo exhibit.

Because so much green design talk is generalized, we decided to tackle the issue head-on. What are the practical applications of green construction in a zoo? Most zoos utilize green methods somewhere on site, but usually it's applied in what I call the "easy places": nutrition centers, gift shops, special events pavilions. Places that are typical construction in a non-traditional setting. But the question always comes up...how do we make a green EXHIBIT?

Mariusz and I put our heads together and came up with a list of specific things that can, in some cases, be easily incorporated into an exhibit. In other cases, its more difficult--generally because it costs more up front.

I've included a link to the AZFA 2010_If I Were A Green Exhibit powerpoint presentation, but for those who just want the highlights, here's a list of our top tips:

1. Maximize Recycled Content: Reuse existing structures, spec materials that are recycled or can easily be recycled; Minimize non-recycled or hard to recycle materials like concrete!

2. Use Geothermal Heating / Cooling: In thermally balanced environments, you can utilize this energy to heat / cool buildings and even small pools. Wells can be placed almost anywhere, including beneath the exhibit or building.

3. Use Solar Panels Strategically: Solar panels cost A LOT so use sparingly if at all UNLESS you have extra dollars to spend on green technology, want to create an educational exhibit, or can use to power specific items such as signage, interactives, lighting, gates, etc.

4. Water Recycling: Can be any scale from rain barrels from roofs to zoo wide programs collecting run-off and wash down. Can be used for exhibit wash down, irrigation, and toilet flushing.

5. Use Native Plants: Eliminates irrigation and fertilization needs and can be selected to mimic just about any environment.

6. Use Water Based Chillers instead of Traditional Air Based: More efficient, less noisy, longer lasting. 25% more expensive. A bargain!

Within the presentation, we outlined initial costs, return on investment, and developed imagery to help everyone understand how these green technologies affect the visitor experience.

What is your zoo doing to become more green?

How Animal Behavior Drives Zoo Design

Some designers begin with a poem. Others look at the educational message. Still others envision a place. I always start with the animal. When I start my design process with the animal, I don't literally mean that I sit down with Google (or even--do you remember this--flipping through books!) spending hours researching the animal's natural history. What I mean is that I immediately register what I know about that animal and have that inform all aspects of design. Of course, I've been doing this for a while and I have quite a bit of animal trivia logged away in my own dusty library of grey matter.

But, really, what is it that informs design? What information about an animal is truly useful in creating its surroundings? The subject of animal behavior is a nearly unending panacea of amazing stories, but determining what facts help inform design can be an overwhelming question.

To help you navigate the masses of information available about specific animals, I've condensed the vast subject of animal behavior into six basic categories relevant to zoo designers.

1. Food Acquisition: Are they carnivores, omnivores, or herbivores?

2. Social Structure: Do they live in groups, pairs, or singly?

3. Time of Activity: Are they nocturnal, diurnal, or crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk)?

4. Micro-Habitat: Do they live primarily in trees (arboreal), on land (terrestrial), in water (aquatic), or some combination of any or all of the three?

5. Personality: Are they shy, curious, skittish, indifferent, vicious?

6. Reproduction: Does their reproductive strategy require any particular element in their physical environment?

Each of the above will provide insight into the physical surroundings that will best house an animal in captivity. For example, carnivores tend to exert energy in bursts, spending the rest of the day sleeping. They also tend to prefer the high vantage points where they can scan the horizon and smell the air. Knowing this, we'd immediately suggest providing this carnivore with several high points in their exhibit, preferably where they can be in close proximity to the guest as they sleep. Jungala at Busch Gardens achieves this well with their tiger pop-up--highest point of the exhibit is actually a viewing window!

Another great example is the amazing bower bird. We could easily create just another generic aviary with a gravel floor or concrete basin. But understanding their reproductive behavior would allow us to create an environment whereby they are able to create their own habitat. {Or, more than that, we could re-create one of their creations on the guest side of things in order to illustrate their great ability.}

Beyond these basics, understanding animal behavior encourages us to strive for ever-more enriching environments. To design an enrichment device, or simply to provide a habitat that provides the most basic form of enrichment--choice, requires that you understand the natural history of an animal.

Oftentimes designers who do not have a specialization in animals, jump immediately to the guest experience; creating a place or a story for the visitor. But, we must understand that a good guest experience at a zoological park revolves around the ANIMAL, not the setting we create. People come to the park to see animals. And if the animals look unhealthy or unhappy, the most beautiful ancient Mayan ruins won't save the experience. Look to the animals first. Be inspired by their lives before creating a story, and you'll see that your final product will be by far the best experience possible for both guests and the animals living there.

Every animal has a story. Its our job to tell it.

Resources:

"Integrating Animal Behavior and Exhibit Design" by John Seidensticker and James Doherty

"Part Five: Behavior" from Wild Mammals in Captivity

Zoo Exhibits in Three Acts

Forgive me. This post will not wrap up cleanly. There will be no final conclusion. No simple 5 step process. This post is simply my musings on design philosophy in zoos. So indulge me. But just don’t expect a Hollywood ending. Last night, I took my husband begrudgingly to the movies to watch “Black Swan”--which he was unwilling to see until one of his buddies had seen it and confirmed that it was, in fact, worthy of a watch. To me, it was breathtaking. Mesmerizing. Exhilarating. But this is not a website on film review, so I’ll leave it at that. But, what is relevant is the fact that, a day later, I am still thinking about it. Analyzing what made it appeal to me so much. Obsessed with how it attached itself around my subconscious, seeping into my most mundane daily thoughts. How did it achieve this? What made it so special to me?

The matter is important in the context of zoo design for one simple reason: this level of affect is the goal of zoo exhibits. We are in the business of creating experiences and memories that so tightly hang in your mind that you have no choice but to not only think about the plight of wildlife or the environment, but take action to protect it. That’s the real goal, isn’t it? Name the last exhibit that did this to you. Go ahead. Try.

To say that exhibits rarely achieve this is an understatement. So, on my morning walk through the woods with the dog (and I’ll amend that for today’s walk to ‘on my snowy morning walk’), I continued to obsess. And I think I figured it out.

Think about any story that grabbed you—a film, a book, a campfire tale. Most were told in the familiar and customary three act structure. If you haven’t been to literature class in twenty or so years, here’s the Cliff’s Notes version: a story is divided into three simple parts—the Setup, the Confrontation, the Resolution. A three act structure allows the listener (or viewer) to first empathize or relate to the main character, understand (and care about) the basic problem the story is addressing, then finally celebrate the resolution of said problem. Practically all major movies follow this structure, and most books do as well. It is followed because it works. It’s as simple as that. Now, just because a film or book follows this format, doesn’t mean the story or the execution won’t fall flat, absolutely ruining an otherwise fine idea. There must be more. There must be something that draws you in. You must first empathize with the character (or animal, in our case). You have to relate to him or her. In the first act, we must see a little bit of ourselves in the subject—our failures, our faults, our dreams, our aspirations—or we’ll just not care.

Empathy can carry us only so far, and as we move through the action, or confrontation, something else needs to take hold. We already care about the character, now what makes us hold on? In “Black Swan”, the hook was a purely visceral, physical reaction. This movie was R rated, so the director expertly leveraged sex, drugs, and pain (which I’ve never seen, nor will I, I’m guessing, ever see in a zoo setting!), but combined with the familiar Swan Lake melodies and simple beauty of dance, the body was fully engaged.

This movie was about evoking a physical reaction, every bit as much as it was about the emotional. And nothing I’ve ever seen brought the two together as well as during the resolution of the film. Built into a tidal wave of chaotic flurry, where every frame was an expertly composed visual feast, and moment after moment brought tension and exhilaration to its absolute apex, then, just as we believe we can take no more, the film concluded. Right there. Right at the peak. Leaving you breathless, body abuzz in euphoria. I left the theater alight. Grinning from ear to ear despite the desperately tragic film I’d just experienced. And I’m still thinking about it. Still wondering how we achieve this kind of attachment to zoo exhibits. How we achieve this moment of perfection.

Rotation Exhibits: How To Guide

The idea of rotating animals through several exhibits as a means of enrichment and variability is a relatively new one. The popularity of the idea is widespread, despite the requirements of large spaces, intensive staff involvement, and complex (or flexible) holding facilities.

Generally, we've been incorporating some sort of rotation capability in all of our exhibits for the past several years. If the staff is willing, the advantage is great: providing several smaller exhibits in which to rotate through the animals during the day provides active animals, which in turn, provides engaged guests.

Generally, we've been incorporating some sort of rotation capability in all of our exhibits for the past several years. If the staff is willing, the advantage is great: providing several smaller exhibits in which to rotate through the animals during the day provides active animals, which in turn, provides engaged guests.

The upcoming Louisville Zoo Glacier Run exhibit takes full advantage of this type of exhibitry. Despite the main exhibit area being on the small size, the bears here will have several play areas away from the main exhibit, thereby increasing the overall territory of the animals. The downside to this is casual visitors may not understand the complexity of the bears' lifestyle, and may judge the exhibit as inadequate.

However, understanding how to incorporate this important concept will enhance most zoo exhibitry, and many times, is a creative solution to a tricky problem. Read more about rotation from da man, Jon Coe, here.

The Next Zoo Design Revolution?

Landscape immersion, which is a type of design intended to "immerse" the visitor in the same natural habitat as the animal, effectively began with the Woodland Park Zoo's gorilla exhibit. Created by zoo design godfathers Grant Jones and Jon Coe as a collaboration with Woodland Park then-director David Hancocks and biologist Dennis Paulson, they coined the term landscape immersion, and thus began the philosophical shift from a homocentric view of zoos to a biocentric view. We now spend massive amounts of resources re-creating "natural" places and cultural phenomena, in an effort to connect people to the earth; to inspire respect of natural places. Back in 1978, this style of design was fresh, new, innovative, revolutionary; nearly thirty years later, the style has become so a part of zoo culture that any exhibit not designed in this manner is questioned for its validity and chances of success. However, should landscape immersion continue to be our design standard? How do we push to the next step beyond landscape immersion?

True and successful landscape immersion requires designers to experience a habitat first-hand before beginning to design a re-creation of it. They research the essence of the habitat, the ecosystem structure within the habitat, and the natural ebbs and flows the habitat would undergo. The animal is an integral part of the ecosystem, not just the centerpiece of a painted scene. The visitor is whisked away to another world, drastically different from the asphalt sidewalks and ice cream shops of the zoo midway. Today's landscape immersion is, too often, not this. Today's landscape immersion usually means planting the visitor space with the same plants as seen in the animal exhibit, and using props from a culture as shade structures, means to hide back-of-house buildings, and educational interpretives. Moreover, today's visitor to a modern zoo no longer has their breath taken away by a landscape immersion exhibit; they simply expect to be immersed in an animal's habitat. The magic of landscape immersion is gone. Along with that, the opportunity to educate and inspire is waning, because, as Coe has said himself, "Only the emotional side, in the end, has the power to generate changes in behavior" (Powell, 1997). If the "oh my" moment is gone, does education stand a chance?

Landscape immersion does not generate longer experiences, as commonly believed. This can easily be shown true by simply observing visitor behavior at exhibits. After studying visitor length-of-stay time at viewing areas, little to no difference can be observed between the old, concrete moated tiger exhibit at Philadelphia Zoo and the landscape and cultural immersion tiger exhibit at Disney's Animal Kingdom. The average maximum stay time of 90 seconds has been consistently shown through observations at other exhibits as well, including the gorilla exhibit and bongo exhibit at Cincinnati Zoo, and the polar bear exhibits at Detroit Zoo and Louisville Zoo. Despite renovations and millions of dollars spent on landscape, rockwork, and interpretives, the most we can expect of our visitors is a minute and a half. Is this time shorter now than at immersion exhibits in the early 1980's? What can we do now to increase this time? Or, what can we do to get the most impact for our minute and a half?

One of the biggest complaints against landscape immersion is the difficulty, generally, in spotting and clearly seeing the animals. Therefore, proximity to animals should be a chief concern in exhibit design. Visitors want to experience something special. They want to do something no one else gets to do; something they have never done. Most importantly, in doing these things, visitors feel connected to the animals. Creating the connection should be of the utmost concern for designers and zoos.

Another component lacking in modern zoo design (not just landscape immersion specifically) is the integration of behavioral enrichment into the basic design process. Too often behavioral enrichment is an aspect of the exhibit that is not addressed by zoos to the architectural designer, even if the behavioral enrichment program is being developed concurrently. Most zoos still see the enrichment program as a separate aspect of the new exhibit to be implemented by the keepers after the exhibit is opened. Most architectural designers are ignorant to the importance of behavioral enrichment as a means not only to increase the health and welfare of the animal, but also in creating an active exhibit with active animals, which translates into longer stay times. Thus, enrichment generally is not addressed as an aspect of design, and ultimately we see beautiful new landscape immersion exhibits with large orange boomer balls and blue plastic barrels. Can these be considered cultural props? Recently, behavioral enrichment has been integrated beautifully into primate exhibits, but what about ungulates and big cats?

Connection creation and enrichment are the two most important issues that we must address in order to move beyond landscape immersion. The complexity of stepping beyond landscape immersion may seem a daunting task. However, the essence of the next successful step will be in creating "novelty"-something new or unexpected. Novelty to visitors, both within every new exhibit they encounter, as well as within the same exhibit upon repeat visits. We must create novelty to animals, both in new enrichment devices and methods, as well as within their own habitats. We need to make adaptable habitats that can be changed on a daily, weekly, monthly or seasonal basis. We need to make experiences for the visitor and animal that they can share, becoming intuitively novel, since every person or animal will react slightly different in new situations. Thus, our new exhibits will stay new, increasing visitor repeat attendance, and discouraging cookie cutter exhibit design.

But how do we begin to do this? In addressing the issues of connection creation and incorporation of enrichment into design, the first and most critical step will be to develop stronger relationships between architectural designers and zoo staff. Designers need to be educated by the keepers on animals' behaviors, both in the wild and in captivity, as well as on methods of behavioral enrichment. Designers should spend a day or two working side-by-side with the keepers as "keepers for a day." This will help designers to not only understand the needs of the keepers in their daily work routines, but also to help create bonds between designers and the animals whose homes they are creating. The zoo staff has a passion for animals that most architectural designers are lacking. This passion needs to be shared and experienced by the designers.

In "novelty-based" design, zoos and designers need to work together to develop new methods of enrichment and test them before integrating them into design. Design schedules and budgets should include a phase for enrichment development and testing, wherein the designers work with the keepers to create prototypes to be tested with the animals. If the zoo is designing exhibits for animals they currently do not have in collection, partnerships should be developed to test enrichment devices at other zoos with those animals. These findings should be recorded scientifically and published for the entire zoo community to share. If the zoo uses training as enrichment, the designers need to experience training sessions and clearly understand the need and utility of the training. Keepers and designers should be discussing how all of these methods can be displayed on exhibit.

Specific enrichment goals need to be addressed at design kick-off meetings, making numerical goals for incorporating enrichment devices and creating new methods. Enrichment must be seen as a philosophical aspect of design, incorporated into the master planning process, because if animals are active and happy, visitors will become more engaged. Enrichment must be planned not only for the opening day of the exhibit, but for the future of the exhibit as well. Animals become acclimated to enrichment devices and stop using them. We must plan for this, developing phasing plans for enrichment, and flexibility of the exhibit design for novelty of the environment. Most importantly, after the construction is complete, studies must be conducted to determine the successes and failures of enrichment techniques. These results should be shared with the zoo community, and especially, the designers.

Secondly, the "novelty-based" design process must become "connection-centered," not visitor-centered or animal-centered. Connections are created both by proximity and by experience. Landscape immersion began to explore this idea by attempting to have visitors and animals in the same habitat, thus experiencing the same things. However, in landscape immersion, we don't experience the same things at all. As visitors, we have a choice to move into a different area, to eat ice cream or hot dogs, to sit and watch the gorillas or to go see the penguins. We don't swim in the same water as the polar bears and we don't get to swing around on ropes like orangutans. What if we started creating these shared experiences? Can we make environments for animals and visitors that are truly similar? What if the actions of a visitor change the environment for the animal? What if the actions of an animal change the environment for the visitor? No longer would we be bound by the idea that the habitat must look like the animals' wild habitat. We could make it look like any thing, any place, any time, as long as the visitor and animal are engaged and ultimately, connected.

We have already seen a movement starting to push beyond landscape immersion, and, in some instances, toward "novelty-based" design. Several new exhibits, including the St. Louis Zoo ‘Penguin & Puffin Coast' exhibit and the San Francisco Zoo's ‘Lipman Family Lemur Forest', utilize natural habitat but also incorporate distinctly non-immersive elements, and are exceedingly successful. These exhibits focus on getting the visitor close to the animals (connection-centered) and being surrounded by active animals (behavioral understanding and enrichment incorporation). This experience, which will be different and therefore novel upon each visit, makes these exhibits extremely emotional and therefore memorable to visitors, and begins to create a connection. These exhibits are a step in the right direction toward "novelty-based" design. Using this type of design, we can move to the next incremental step in the evolution of landscape immersion, keeping the "oh my!" moment, and continuing to educate and inspire our zoo visitors.

Enrichment Based Design, Revisited

Over ten years ago, Jon Coe wrote a paper outlining the upcoming breakthroughs in exhibit design, using enrichment based (or as he says, activity-based) design. These exhibits have now been opened and are successful. However, ten years from the original date of the paper, designers still have not fully embraced the design concept. Incorporating enrichment devices into an exhibit is one thing; to fully base design on enrichment or activity, is an entirely different animal. As Coe points out, however, design is not fully the designers' decision. A new animal habitat has many stakeholders, and even if the designer supports the idea of basing design on enrichment, the entire team of administrators, keepers, curators, and Board of Directors, not to mention all members of the design team, must also agree.

In many cases, the resources (of time, money, and/or space) just aren't there. Many times, the decision comes down to making an immersive environment or making an enriching environment. Unfortunately, many folks in the industry still hold onto the idea that an immersive environment equals animal health and activity, or at least, equal visitor satisfaction. However, active animals are much more powerful than a pretty environment, and we must work on our clients to understand this.

Studying Visitor Behavior

I've written in the previous posts about my experience studying visitor behavior at zoos. Well, I've briefly mentioned it, at least. Although many zoos throughout the U.S. are studying visitor behavior, it is a rare occasion for designers to get the chance to get the first-hand experience of studying how visitors use their designs. I highly recommend doing some informal visitor studies at exhibits you've designed as well as at those you have not. From my past visitor studies, I've learned two consistent lessons:

1. Visitors stay at each viewing station less than 90 seconds. No matter what species is displayed, or how well they are displayed. The only exception is when the animal is extremely active. For example, studying visitors at Disney's Animal Kingdom's beautiful tiger exhibit, I noticed a major spike in visitor length of stay, from the average 90 seconds to upwards of 9 minutes when the tigers had, serendipitously, spotted a rabbit in their enclosure and subsequently went into hunting mode. The experience was mesmerizing, and everyone was swept up into the excitement. This makes me wonder if live feedings shouldn't be more acceptable...but that's another story.

2. Less than 2% of visitors fully read signage. Fully interactive interpretives may be a different story. None of the exhibits I have studied had any of these more modern interpretives.

Researchers at Chicago's Lincoln Park Zoo studied visitor behavior following the opening of their recently opened Regenstein Center for African Apes. The article written outlining their experience supports only one of my lessons...No one reads signs. However, their visitor stay time far exceeded anything I've encountered (although they measured their length of stay differently, by measuring the full exhibit stay time rather than per viewing window).

That researcher in the ape house? She was studying you.

By James Janega

Tribune staff reporter

April 26, 2007, 10:57 PM CDT

The animal behaviorists at Lincoln Park Zoo have given simple tools to gorillas and taught chimpanzees to navigate computer touch screens, but their latest experiment involved a primate so intelligent and cagey, it was going to take work to outsmart it.

The subject was people and to measure their behavior at the zoo's ape sanctuary without them catching on, a 24-year-old zoo office worker with girl-next-door looks would have to slip on quieter shoes, wear muted colors and follow people in secret by watching their reflections on glass.

Starting last spring, conservation assistant Katie Gillespie spent a year clocking visitors' stays in the Regenstein Center for African Apes, noting where people loiter and what they look at.

With her boss, Steve Ross, she frowned when people ignored interpretive signs and took smug comfort when subjects were captivated by apes. For months, she and Ross hoarded statistical glimpses into how humans prefer to learn about chimpanzees and gorillas.

It was all very scientific, not to mention fun and kind of sneaky.

In the course of 476 observation sessions over 12 months, Gillespie and Ross learned that everybody likes watching apes and nobody likes reading signs. They found people love to pose with ape sculptures, and that parents all too often make up answers for their children.

And they proved the best way to fool people is to let them fool themselves.

"I've had people ask me what I'm doing," Gillespie said. "I tell them I'm taking behavioral data. Then they ask me questions about the animals."

Gillespie, who has a bachelor's degree from the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point, trained in natural resource management and has a day job as exotic as her office cubicle.

As for zoo experience, she made signs for a raptor walk at the Marshfield Zoo near Wausau. Her real job at Lincoln Park Zoo involves administrative tasks at an office a few minutes away from the ape building.

But on Feb. 21 last year, she climbed into an unlit, concrete mezzanine at the Regenstein Center, looked out windows tailored for watching animals, and listened as Ross told how to follow people without them knowing.

It was a slow morning in the ape center, a tough time to avoid notice. But there are tricks of the trade, Ross reassured her.

Downstairs, other conservation assistants were using Palm Pilots to study apes. Hold one, and people will assume you're watching chimps, he said. Get ahead of people and let them pass you. Use reflections and peripheral vision.

He used the word "spy." Gillespie got the job after biologists told Ross they'd rather watch apes, not people.

Ross had done this before, in 2000, but inside the old, round, dark Great Ape House, a cinch compared with the Regenstein Center's bright, open floor plan. This new place, built in 2004, upped the ante. You could get caught.

"I've had an awful time getting people to do this," Ross told her.

Gillespie stuffed printed explanations of the study in her pocket that included Ross' phone number, to hand out in case she was confronted. In those first days, she wondered if it was going to work.

"It's almost impossible," she exclaimed early on. As a practice subject approached the entrance, she hurried down the metal stairs to the floor below, her high-heeled pumps clanging on each step. The ringing subsided just as the subject opened the door below the mezzanine.

"We gotta get you some sneakers," Ross told her later.

By May and June, when school groups crowded the floor so thoroughly it was hard to move, Gillespie was an expert. She followed kids in camp groups in July, vacationers in August and September, and aborted an observation only once-when a young couple started making out.

It turned out the challenge wasn't getting caught, she found. It was battling exasperation. People complained when the apes sat around, in the middle of rest cycles clearly defined on nearby signs. Parents made up answers to kids' questions. People made mistakes, and no one corrected them.

"You hear people asking questions that are written all over every sign everywhere," Gillespie said of those moments. "But you can't influence them."

So she just observed-always the fifth person to enter after the last subject left. The sessions were always anonymous. Regulars were ignored.

Her shortest follow came on a sunny Sunday afternoon in June: a girl in an organized group who stayed 2.3 minutes while a heavy crowd shoved through the air-conditioned building. The longest visit was in December, a woman with children who relaxed for 116 minutes. January brought visitors in a steady, unhurried rhythm. Often, the subjects stood at Gillespie's elbow without knowing.

One was the man in the blue coat. At midday on Jan. 24, 2007, Gillespie, wearing moccasins, padded down the stairs from her mezzanine perch to beat him to the chimp enclosure.

Behind her, the man watched JoJo's gorilla troop, then breezed past an interpretive display to study Hank and his group of chimps, where he planted himself in front of Gillespie to do it.

She wore a zoo badge and appeared to watch the animals. Every 15 seconds, her Palm Pilot chirped a reminder to note the man's behavior: "Locomote," "Watch Chimps," "Photo Chimp."

The terminology was borrowed from animal behaviorists, and the man in the blue coat had no idea the soft beeping was for him.

Over 29 minutes, Gillespie took two pages of behavioral notes. The man watched both gorilla troops, talked to docents, took more pictures and left. The list recorded only movement, location and activity.

But on the floor it looked like more. It seemed like deep fascination.

A full analysis is months away, but some things are clear.

Watching apes was the most popular behavior, and visitors lingered more in the airy naturalistic environment than in the previous concrete-and-steel building.

The most popular exhibit elements were life-size hands and busts of various apes, which people touched and photographed regularly. The average visit was 15.5 minutes.

But many zoo interpretive standbys fell flat. Just about everyone ignored a looping video describing behavioral research on apes at the adjoining Lester E. Fisher Center. They likewise ignored graphics beside actual apes that described a "day in the life" . . . of apes.

People learned by watching apes that acted as they do in the wild.

It was an epiphany for Gillespie that came on one of her last observations. In February, a young mother brought her 1-year-old daughter to the chimp enclosure where Kipper, a young male, showed off for the girl through the glass. The mother and daughter were delighted by the connection.

"You knew that this was such a special moment that they would remember," Gillespie said. "And maybe that would be more impactful. Even though they weren't reading signs."

jjanega@tribune.com Copyright © 2007, Chicago Tribune

I fully believe every time a new exhibit is proposed, designers should spend at least one day watching how visitors use the old exhibit, and / or similar exhibits (to that proposed) at other zoos. Additionally, we need to instate an industry standard of post-opening visitor behavior research. Most institutions do some amount of study post-opening, but that information is rarely passed onto the designers. Designers need to be proactive and spend some time at their creations, truly critiquing the successes and failures. Only then will we be truly able to truly be experts.

Natural Enrichment Ideas for Exhibit Design

We've all been witness to, and some of us may be to blame for, the red boomer balls in tiger exhibits or the blue barrels in the polar bears habitat. I've heard guests laugh about beer kegs in the bear exhibits, implying in some manner that the bear's an alcoholic. Positively enjoyable for the guests and the bear, but still a problem as they bring a wholly artificial element into an otherwise "natural" setting.

In an effort to curb these disruptions in our suspension of disbelief in an immersive zoo exhibit (in other words, in order for us to get rid of any sign that we are, in fact, in a zoo, and not in Borneo or Alaska), we need to start planning the enrichment as a part of the exhibit design process with the keepers.

Jon Coe wrote a nicely illustrated paper for the Australasian Regional Association of Zoological Parks and Aquaria conference back in 2006. Within this paper not only does he clearly outline several concepts for enrichment devices within exhibits, but also lays out some general guidelines. Take a look!

Learning at Zoos...Do they get it?

Learning is the culmination of perceptions and knowledge. It is assessed by changes in attitude and behavior (Powell, 1969). Therefore, creation of meaning is a form of learning. "Learning...is the means through which we acquire not only skills and knowledge, but values, attitudes, and emotional reactions" (Taylor, 2002). As educators know, people learn by different means: visual clues, reading, hands-on experience, imitation, and so on. Successful learning generally occurs through repetition and utilization of multiple channels of education (Powell, 1969). In assigning meaning to a zoo exhibit, a person can learn through contextual clues of the exhibit, written signage, hands-on interpretives, and docents. Although several channels of learning are available to a zoo visitor, it is important to remember that successful education depends on the "inclination and ability to receive and to respond" to these education channels (Taylor, 2002). Understanding that visitors may or may not be visiting the zoo with the intention of learning is a first step to more successfully educating the visitors. This means that we must not only provide interesting signage and interpretives, but we have the daunting task of ensuring that every aspect of the exhibit follows the educational message we are intending to send.

Additionally, we have to create an environment where learning is fun. Usually, people don't come to the zoo to read. Walking up to an exhibit with a slew text on a sign can be overly intimidating to visitors. I've done studies on visitor behavior and have found that barely 2% of visitors completely read text panels next to zoo exhibits. Most glance at the sign to learn the name of the animal or some other easily accessible information, depending on how the sign is laid out, like where its from or what it eats. Therefore, learning and meaning assessment is generally accoomplished through visual cues and sensorial experience, and not intentional educational signage.

Because of this, many designers live by the notion of "Edutainment" (educational entertainment). Obviously, this style of design requires us to develop an in-depth story for experience alongside the equally important educational "big idea". The two intertwine and support each other. Recently, edutainment has meant an engaging, true to life environment, completely immersing the visitor in the natural habitat of the animal along with the region's cultural cues. However, I question if we cannot spread our wings a bit from the reality of a specific place to encompass more of a fantasy feeling, to entertain, while still meeting our educational goals.

Ultimately, learning in zoos and aquariums (and museums, as well) must be recongnized as a crucial component in our designs. Being responsible designers means to be aware of the meaning our guests assign to the experience they just encountered. Did the rollercoaster through the orangutan exhibit subconsciously lower the value of the orangutan to the visitor, or did it heighten the excitement of the experience thereby increasing the excitement associated with all aspects of the experience, including the animals related? Did the addition of text heavy graphics throughout the exhibit make the exhibit less fun for the visitor, or make the information less accessible to them? What about that trench drain at the foot of the underwater viewing area? How does that affect the viewer's experience?

At the heart of the issue is why we are doing what we do. Connection. If someone doesnt entirely get all of the educational goals at the end of their experience, but do walk away thinking, Man, those Orangutans are cool! Then we did our job, in my humble opinion.