In 2018, I was honored to join forces with an extraordinary group of leaders of small zoos and aquariums to present a Q&A panel at the AZA Annual Conference on the unique challenges and opportunities of being a small institution. The session was well-attended, and a great energy and discussion occurred revolving around pre-determined questions and questions harvested from the live audience via text and good old-fashioned raising of hands.

Although the session was 90-minutes, we still weren’t able to answer everyone’s questions. Luckily, one of our esteemed panelists, Jessica Hoffman-Balder, General Curator, has generously taken on a few of those unanswered questions providing information related to hybrid institution Greensboro Science Center in North Carolina.

1. How do you make your smaller institutions heard at an AZA level when there are so many larger institutions with a larger voice?

So I’m not sure in what context this question would be referring to. In my experience, I see AZA as an opportunity for small institutions to have just as much of a voice as larger ones. It’s about being active in participation and inserting yourself in dialogue regarding topics, or striving to obtain roles in committees, TAG’s, SAG’s, etc… I actually see a good diversity of small and large institutions reps as AZA inspectors, commission members, and within the steering committees I am on. Also, being active on AZA network discussions is a great place to start.

2. What spaces are you using for:

Nursing Station: We do not have an official nursing station, but currently we have a small meeting room that is rarely used by staff, but is made available to nursing mothers if they ask about a space at our front desk. They are given access to the room, and there is a discreet hang tag with the letter “N” on it that is hung on the door so that staff are made aware that the room is in use. In the room are several rocking chairs, small table, etc. Before this space, we utilized a small utility closet that we made into a comfortable spot with a single rocking chair, lamp, etc. We also have had other locations that were more private on site that became natural nursing areas such as a secluded court-yard spaces and a rarely used staff hallway.

Quiet Rooms / Adult Changing Stations: Outside of the nursing room, we do not have dedicated spaces for anything else. However, if any guest inquires about this kind of need, we will gladly open up any classroom space, meeting room, or other unoccupied location to assist them. We will have a staff member “stand guard” to ensure privacy until the guest is finished. We will be adding our first family restroom to our zoo expansion in 2020 to help with this.

3. What are some ways to drive traffic during slower seasons?

Being a museum and aquarium as well as a zoo, we are lucky in that we are not as impacted by a slow season as others may be. We do have a significant amount of indoor space which helps us greatly during cold or inclement weather. We do also have a large great room where we can host interesting traveling exhibits. They generally bring good numbers and we try to time these openings during fall to boost numbers and capitalize on school programming. We try to provide more program opportunities also in the slower months and make connections to holidays and snowy weather via social media to highlight fun event days or great photo ops. We also are investigating a holiday lights program for next winter, which has been very successful for other institutions.

4. What do you offer in terms of membership and/or annual pass holders?

These are our benefits:

Member Benefits - Valid for a full year!

Free general admission to the Greensboro Science Center (GSC).

Free admission to over 300 ASTC facilities.

Free or discounted admission to over 150 AZA facilities.

Discounted SKYWILD admission.

Discounted general admission ($11.50) for guests of members.

$1 off OmniSphere shows for members and their guests.

Expedited members-only entry.

A 20% discount on each purchase in the TriceraShop.

A 10% discount on each purchase in The Meerkat Café.

Discounts on GSC birthday party packages.

Invitations, coupons and discounts to special events, exhibit openings and new OmniSphere shows.

Priority registration and discounts for workshops and camps.

Free newsletter and email updates.

Special discounts at participating local businesses.

Cost:

We do it by number in party from 1-10 with price range of $30.35-$232.69 for city residents and 33.72-$258.55 for non-residents. A single ticket entry for us is normally $13.50 for adults and $12.50 for seniors and children.

We do also offer a Business Membership program and details on that can be found on our website.

5. How can consultants help?

The only areas where we have used consultants has been in helping us with our capital campaign and with our marketing and P.R. Though we have both development and marketing staff, these were the two areas we felt were most important in getting outside assistance. We knew we had a good product, but struggled with getting people to know about us. So far, the cost and effort have been worth it. We just wrapped up a very successful capital campaign where we far exceeded our fundraising goals. We also just closed out a record breaking attendance year and our previous record had been when we opened our new aquarium. We have seen a great rise in guests from outside our immediate community and feel we have transitioned into more of a tourist destination.

6. How do you balance catering to the local community and capturing tourist revenue?

I think taking a look at your complete package of offerings is one way to balance both. Our local community is more likely to be our members and also more likely the guests to participate in our extra activities like camps, special events, and other unique programs. Gearing the promotions and advantages of these programs to our local community is our focus. For tourists, we try to focus more on our day-of experiences like ropes courses or BTS tours and focus advertising to different locales like airports and travel centers. We also try to do joint promotions with other large events that may be in our area and already drawing in an outside crowd.

7. Are you AZA accredited? Why or why not?

Yes, since 2007. This was a high priority for our new director that came in shortly before this time. He had been from other AZA facilities and recognized the importance of striving for and achieving best practices which in turn create better guest experiences and increased attendance and revenue. Additionally, becoming AZA accredited provides a wealth of opportunities to gain resources from other staff and institutions, work with sustainable animal collections, grow in staff professional development, and have more of a collective power in conservation and research.

8. How large is your staff?

We currently have 49 FT positions and 95 part-time.

9. Do you find staff use a small facility as a stepping stone to gain experience and then leave when trained up? If so, how do you retain experienced staff on a limited budget?

Certainly, some staff use small facilities as a starter place to grow their experiences. However, I think that becomes a great opportunity for small facilities to get known and recognized in the larger AZA community if you are sending well trained staff out into the larger network. I also see just as many folks hitting a point where they want to step back from the large facilities and find better purpose and meaning with smaller institutions. We personally have had very little issue with staff retention and I, in fact, was one of those that sought out a smaller facility where I felt like I could be a part of something more in my position. Your culture and community also play a huge part in retention and regardless of pay, staff will have a very hard time leaving a job they love at a place they love with co-workers they love. Finally, we also make a concerted effort to invest heavily in the staff we have. We may not draw the most experienced applicants initially, but we are very supportive of staff development and training. Some may be afraid of doing this and then losing those folks to better jobs but we have found that those staff members really appreciate the attention and effort put in to them and instead, it grows their loyalty.

10. Small facility = small advertising budget. What has worked best?

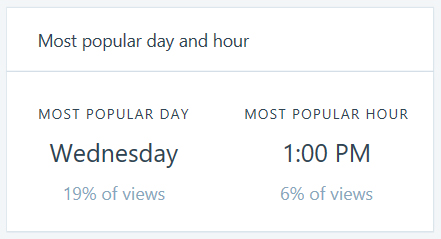

Well, certainly social media efforts have been one of the most affordable and effective ways to grow our brand. We have a variety of campaigns that differ depending on the platform but include Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube the most. We have phased out Twitter as it had the lowest response rate. We also utilize a variety of print adds, primarily through key local publications like parent magazines, and our state magazine. This past year, we did hire a consulting group to help us determine where we would be most effective in marketing. Though this took a significant portion of our budget, it did also help us determine where we should and should not be spending our money and how visitors are best receiving information. We have used this data to start some more targeted media advertising through smart-phone ad beacon technology. This has proven highly effective. Also, just boots on the ground, getting out in your community, really helps remind folks that you are there. Though this takes staff time, financially, it can be very affordable to make appearances at local events.

The Owl at the Table blog posts are on-going features focusing on interviews with the passionate staff from small institutions.

A snippet of my quite

A snippet of my quite