My company is just me. And that’s by design. I do not intend to hire employees and I purposefully keep my fees and client volume low. I view it as a complete success, but given the common perception of “business success,” I often wonder if others would agree… In this article, I outline my business strategy of Growing Small as an alternate measure of success.

Tips for Working with Introverted Consultants

Master Planning 101

As a designer dedicated to the long-term planning of zoos and aquariums, I’ve had to explain the process of master planning many times, and although every zoo and aquarium is different, the best master plans (i.e. those which have been implemented) always follow a similar structure. In this post, we address the most commonly asked questions to help you understand what master planning is, when is the right time to start, and who should be involved.

Addressing DEAI in Zoos and Aquariums

Zoos and aquariums have a long way to go related to being community assets that are truly reflective of their surrounding communities. Recent discussions in the AZA suggest that instead waiting for ‘best practice’ solutions, that individual organizations must start somewhere acknowledging that our strategies will evolve as we all learn the most productive ways to approach DEAI.

Owl at the Table--Perspectives from the Small & Mighty: Jessica Hoffman-Balder, Greensboro Science Center

In 2018, I was honored to join forces with an extraordinary group of leaders of small zoos and aquariums to present a Q&A panel at the AZA Annual Conference on the unique challenges and opportunities of being a small institution. The session was well-attended, and a great energy and discussion occurred revolving around pre-determined questions and questions harvested from the live audience via text and good old-fashioned raising of hands.

Although the session was 90-minutes, we still weren’t able to answer everyone’s questions. Luckily, one of our esteemed panelists, Jessica Hoffman-Balder, General Curator, has generously taken on a few of those unanswered questions providing information related to hybrid institution Greensboro Science Center in North Carolina.

1. How do you make your smaller institutions heard at an AZA level when there are so many larger institutions with a larger voice?

So I’m not sure in what context this question would be referring to. In my experience, I see AZA as an opportunity for small institutions to have just as much of a voice as larger ones. It’s about being active in participation and inserting yourself in dialogue regarding topics, or striving to obtain roles in committees, TAG’s, SAG’s, etc… I actually see a good diversity of small and large institutions reps as AZA inspectors, commission members, and within the steering committees I am on. Also, being active on AZA network discussions is a great place to start.

2. What spaces are you using for:

Nursing Station: We do not have an official nursing station, but currently we have a small meeting room that is rarely used by staff, but is made available to nursing mothers if they ask about a space at our front desk. They are given access to the room, and there is a discreet hang tag with the letter “N” on it that is hung on the door so that staff are made aware that the room is in use. In the room are several rocking chairs, small table, etc. Before this space, we utilized a small utility closet that we made into a comfortable spot with a single rocking chair, lamp, etc. We also have had other locations that were more private on site that became natural nursing areas such as a secluded court-yard spaces and a rarely used staff hallway.

Quiet Rooms / Adult Changing Stations: Outside of the nursing room, we do not have dedicated spaces for anything else. However, if any guest inquires about this kind of need, we will gladly open up any classroom space, meeting room, or other unoccupied location to assist them. We will have a staff member “stand guard” to ensure privacy until the guest is finished. We will be adding our first family restroom to our zoo expansion in 2020 to help with this.

3. What are some ways to drive traffic during slower seasons?

Being a museum and aquarium as well as a zoo, we are lucky in that we are not as impacted by a slow season as others may be. We do have a significant amount of indoor space which helps us greatly during cold or inclement weather. We do also have a large great room where we can host interesting traveling exhibits. They generally bring good numbers and we try to time these openings during fall to boost numbers and capitalize on school programming. We try to provide more program opportunities also in the slower months and make connections to holidays and snowy weather via social media to highlight fun event days or great photo ops. We also are investigating a holiday lights program for next winter, which has been very successful for other institutions.

4. What do you offer in terms of membership and/or annual pass holders?

These are our benefits:

Member Benefits - Valid for a full year!

Free general admission to the Greensboro Science Center (GSC).

Free admission to over 300 ASTC facilities.

Free or discounted admission to over 150 AZA facilities.

Discounted SKYWILD admission.

Discounted general admission ($11.50) for guests of members.

$1 off OmniSphere shows for members and their guests.

Expedited members-only entry.

A 20% discount on each purchase in the TriceraShop.

A 10% discount on each purchase in The Meerkat Café.

Discounts on GSC birthday party packages.

Invitations, coupons and discounts to special events, exhibit openings and new OmniSphere shows.

Priority registration and discounts for workshops and camps.

Free newsletter and email updates.

Special discounts at participating local businesses.

Cost:

We do it by number in party from 1-10 with price range of $30.35-$232.69 for city residents and 33.72-$258.55 for non-residents. A single ticket entry for us is normally $13.50 for adults and $12.50 for seniors and children.

We do also offer a Business Membership program and details on that can be found on our website.

5. How can consultants help?

The only areas where we have used consultants has been in helping us with our capital campaign and with our marketing and P.R. Though we have both development and marketing staff, these were the two areas we felt were most important in getting outside assistance. We knew we had a good product, but struggled with getting people to know about us. So far, the cost and effort have been worth it. We just wrapped up a very successful capital campaign where we far exceeded our fundraising goals. We also just closed out a record breaking attendance year and our previous record had been when we opened our new aquarium. We have seen a great rise in guests from outside our immediate community and feel we have transitioned into more of a tourist destination.

6. How do you balance catering to the local community and capturing tourist revenue?

I think taking a look at your complete package of offerings is one way to balance both. Our local community is more likely to be our members and also more likely the guests to participate in our extra activities like camps, special events, and other unique programs. Gearing the promotions and advantages of these programs to our local community is our focus. For tourists, we try to focus more on our day-of experiences like ropes courses or BTS tours and focus advertising to different locales like airports and travel centers. We also try to do joint promotions with other large events that may be in our area and already drawing in an outside crowd.

7. Are you AZA accredited? Why or why not?

Yes, since 2007. This was a high priority for our new director that came in shortly before this time. He had been from other AZA facilities and recognized the importance of striving for and achieving best practices which in turn create better guest experiences and increased attendance and revenue. Additionally, becoming AZA accredited provides a wealth of opportunities to gain resources from other staff and institutions, work with sustainable animal collections, grow in staff professional development, and have more of a collective power in conservation and research.

8. How large is your staff?

We currently have 49 FT positions and 95 part-time.

9. Do you find staff use a small facility as a stepping stone to gain experience and then leave when trained up? If so, how do you retain experienced staff on a limited budget?

Certainly, some staff use small facilities as a starter place to grow their experiences. However, I think that becomes a great opportunity for small facilities to get known and recognized in the larger AZA community if you are sending well trained staff out into the larger network. I also see just as many folks hitting a point where they want to step back from the large facilities and find better purpose and meaning with smaller institutions. We personally have had very little issue with staff retention and I, in fact, was one of those that sought out a smaller facility where I felt like I could be a part of something more in my position. Your culture and community also play a huge part in retention and regardless of pay, staff will have a very hard time leaving a job they love at a place they love with co-workers they love. Finally, we also make a concerted effort to invest heavily in the staff we have. We may not draw the most experienced applicants initially, but we are very supportive of staff development and training. Some may be afraid of doing this and then losing those folks to better jobs but we have found that those staff members really appreciate the attention and effort put in to them and instead, it grows their loyalty.

10. Small facility = small advertising budget. What has worked best?

Well, certainly social media efforts have been one of the most affordable and effective ways to grow our brand. We have a variety of campaigns that differ depending on the platform but include Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube the most. We have phased out Twitter as it had the lowest response rate. We also utilize a variety of print adds, primarily through key local publications like parent magazines, and our state magazine. This past year, we did hire a consulting group to help us determine where we would be most effective in marketing. Though this took a significant portion of our budget, it did also help us determine where we should and should not be spending our money and how visitors are best receiving information. We have used this data to start some more targeted media advertising through smart-phone ad beacon technology. This has proven highly effective. Also, just boots on the ground, getting out in your community, really helps remind folks that you are there. Though this takes staff time, financially, it can be very affordable to make appearances at local events.

The Owl at the Table blog posts are on-going features focusing on interviews with the passionate staff from small institutions.

Happy Anniversary! 10 Years of DesigningZoos.com

Can you believe this summer marks ten years of my little corner of the internet talking about design and the future of zoos and aquariums? Although my posting has become more infrequent as my professional life has evolved, you--my supportive and sometimes thoughtfully critical reader--remain constant. I owe you a huge Thank You for reading my ramblings, and contributing your thoughts. For funsies, I thought we'd review a few of the highlights from the past 10 years and over 200 posts!

Top Ten All-Time-Most-Popular Posts (by visits)

10. "Visitors: An Overlooked Species at the Zoo" (2013) by guest blogger and colleague, Eileen (Ostermeier) Hill. Discusses the critical importance of visitor studies at zoos, some hurdles to studies, and the role of designers relative to visitor studies.

9. "The Future of Zoos: Blurring the Boundaries" (2014) a second entry by guest blogger and obviously brilliant colleague, Eileen Hill. Powerpoint presentation with script about trends in zoos today and how they may play out into zoos of the future. Eileen proposes zoos of the future will by hybrids of multiple science based institutions.

8. "St. Louis Zoo's SEA LION SOUND" (2012). Showcasing the then-new exhibit at the Zoo including fly-thru video, photos of new exhibit, and interview with one of the architects from PGAV Destinations who helped bring the design into reality.

7. "SAFARI AFRICA! Revealed at Columbus Zoo" (2012). Announcement of the ground-breaking of the eventual AZA Top Honors in Design award-winning Heart of Africa (renamed). Includes renderings and site plan.

6. "Underdogs: The Appeal of the Small Zoo" (2013). Exploration of what makes small zoos so appealing to visitors, and meaningful to work for as a designer. Features Binder Park Zoo, Central Florida Zoo, and Big Bear Alpine Zoo.

5. "In Marius' Honor" (2014) by guest blogger and now Project Manager at the esteemed Monterey Bay Aquarium, Trisha Crowe. Trisha explores her emotional reaction to the Copenhagen Zoo's disposal of Marius the giraffe, and implores readers to support zoos, no matter your stance on animal rights.

4. "Small and Sad: Dubai Zoo's Relocation on Hold Again" (2009). Occurred to me today, should have been title "Small and SAND", but the sad state of the old zoo is what made this post so popular. Includes design plans and renderings--which I am sure are woefully out of date. Anyone have any updates??

3. "How to Become a Zoo Designer" (2014). After about 25,000 emails from aspiring zoo designers asking similar questions, I just went ahead and wrote it up to shortcut a step... Still, feel free to email me--I always write back. Let's be pen pals!

2. "The Next Zoo Design Revolution" (2008). One of my very first posts, which explains the popularity. Some say naïve, some say gutsy look at incremental revolution in zoos. The future of zoos has been examined at least 300 times since this one, but in re-reading, I see some kernels of accuracy. Expect an update soon...

And in the #1 spot....

1. "A Quick Lesson in Zoo Design History" (2008). Perhaps my second post ever, which again explains it's number 1 spot. A not-as-advertised look at zoo design history which, I have a feeling, has been referenced by many of the 25,000 students (above) in their zoo projects. Holla at me if you cited me!

Top Ten Recommended Reads for Zoo Designers (aside from those above)

10. "To Safari or Night Safari" (2008). I'm a sucker for the title. But this post examines the very slow to catch on trend of after-hours programming or extended zoo hours as a feasible method to increase attendance. Post-posting amendment: in particular, this is a great strategy for targeting adults without kids.

9. "Does Winter Have to be a Dead Zone at the Zoo?" (2013). I cheated a little on this one. I didn't actually post to DZ.com, but to my blog at Blooloop.com where many of my more recent posts have been landing. This one discusses another strategy to increase attendance by targeting the most difficult time of year for temperate zoos: winter.

8. "Zoo Exhibits in Three Acts" (2011). Storytelling in zoo exhibits, told through, what else?: a story.

7. "8 Characteristics of Brand Experience" (2018). A new one! Understanding what makes strong brands so very strong is important and applicable to new attractions at zoos and aquariums. Examined through the lens of non-zoo brands, like my fav: OrangeTheory.

6. "Interactivity and Zoos" (2013). Examining the different modes of interactivity that are available in zoos, and how they can be applied to experience. A good primer.

5. "How Animal Behavior Drives Zoo Design" (2011). Starting with animals in design can be overwhelming. What information is pertinent to a designer, and what is just interesting to know. Another good primer for learning the basics of zoo design.

4. "Chasing Big Cats: Snow Leopards and Perseverance" (2017). Being a good designer is about so much more than just having cool ideas and being able to communicate them well. Learn the qualities intangible qualities that make good designers, GREAT. Don't be afraid...hint, hint.

3. "Making Responsible Tacos: Conservation Brand Perception at Zoos and Aquariums" (2015). Adapted from a talk I gave, I examine how aspirational brand should translate to experience in zoos and aquariums using the popular taco analogy. Yum. Tacos.

2. "Five Zoo Innovations that have been around for Decades"Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5 (2014). Again, pulled from Blooloop. A series of 5 posts examining design elements and characteristics that American zoos have been implementing for decades. This series was an angry reaction to the 'revolutionary' design of metal pods floating through a zoo in Europe. A woman scorned...publishes 5 posts to prove how you don't know anything about innovation. Ha!

1. "Zoos in a Post Truth World" (2017). What every zoo and aquarium advocate needs to consider in this continued atmosphere of skepticism, critique, and distrust. As a zoo designer, you must be aware of changing perceptions and the power we have to shape them.

Top Ten Things I Learned in the Last Ten Years (Blogging or Otherwise...)

10. I'm not shy; I'm introverted

9. How to poop in a hole while wearing 3 three layers of snow pants

9a. Always pack enough Pepto tabs (at least 2 per day while away)

8. I'm not good at social media (see: 10 years of blogging and 600 Twitter followers, probably mostly for cat pics)

7. And speaking of cats, the rubbery buttons of a TV's remote control makes said remote an easy tool to remove cat hair from sofas and pants

6. I sleep better when flying in Business Class

5. Always pay the extra money to hire movers to load and unload that U-Haul

4. Writing isn't hard. Just start typing and...

3. Confidence

2. I lose all 'adultness' around ice cream and baby animals

1. Zoo and aquarium people are really the best people in the world.

Here's to many more decades of Zoo & Aquarium design!

With love and respect--

Your friend, Stacey

Chasing Big Cats: Snow Leopards and Perseverance

I’ve always been nervous about meeting new people. Socializing is not my natural state. I hated Santa--coming into our grandparents’ house, demanding me to sit on his lap. I’d run and hide under the dining room table when I heard that jolly ho-ho-ho. My stomach does flops thinking, not about the presentation to 300 people, but of the awkward mingling with conference attendees and fellow speakers before and after. I avoid parties where I don’t know at least three people closely (I gladly host them, happy in the knowledge I can always escape into hosting duties such as serving food or MCing a game). Spending three weeks on a frigid Indian mountainside in December with a handful of strangers who mostly speak languages other than my own was quite possibly the scariest thing I’ve ever attempted.

This post is about leaving your comfort zone. A critical element of personal development—and more importantly, of becoming the best designer you can possibly be.

That morning arriving to Leh, after thirty hours of travel and four flights, I was not ready to sit and drink tea with five strangers—in a country I’ve never been. We made small talk about how the flights were and where we are from. We weren’t sure what kind of tea to drink. What is Masala? Is it with goat’s milk like my friend warned me of? How much caffeine does it have? Do I need sugar??? I didn’t know who actually spoke English and therefore could handle me asking them a question, and who would look at me panicked not understanding what the tall blonde American lady is demanding! I was tired, cranky, but also excited to finally be here. To finally be on the hunt for the elusive snow leopard.

Several days later, after “adjusting” to the elevation of Leh (around 11,000’) and after spending a day together birding around the Himalayan foothills surrounding the town, we loaded up the SUV with our gear to hit the mountains. We headed to our camp in Hozing Valley. Situated among mountain ridges between 12,000 and 13,000’, our base camp consisted of three small sleeping tents (one for each of us), and two larger mess-style canvas tents—one serving as kitchen, one as the dining room. The dining tent had a propane heater; the kitchen had a cook and a cook’s assistant. We had a simple pit-toilet outhouse—a hole in the floor. We had no running water, no heat in our sleeping tents. It was December, and it was cold. Very cold. The coldest night was about -35 F.

The days were filled with hiking nearly vertical slopes among boulders and on gravelly sheep-made paths, to sit in the sun on ridges overlooking the valley. We’d sit for hours, scanning the rocky cliffs with binoculars and spotting scopes. We’d layer up for the frigid morning walks starting at sun up—before the sun passed over the ridges, when accidental water spills turned instantly into icicles. Some mornings--the coldest mornings, I’d be wrapped up so thick, my shadow looked like an astronaut: two wool base layers, two pairs of snow pants on my legs; a wicking shirt, two wool base layers, a fleece vest, a fleece jacket, a down jacket, and a ski jacket on top; a scarf; two hats (one a beanie, and one a thick, (faux) fur-lined Nordic thing); three pairs of socks; a pair of wool gloves beneath a thick set of mittens. At 10:30am, the sun came up over the ridge--its warmth allowed us to remove layers, and caused our feet to sweat as we trekked up several hundred feet of steep slope in astronaut gear. Then, when the sun found its way behind the ridges again at 3:30pm, our toes began to numb as our sweat-soaked socks and boots literally froze.

It was fun. I definitely lost 5 pounds.

But the reward was delivered on the third day: a snow leopard! The build-up to the sighting was screenplay perfection. Our trackers spotted a blue sheep (the snow leopard’s favorite prey), dead on the ridge above our camp. They inspected the frozen carcass and found no obvious signs of trauma, just a dribble of blood at the corner of his mouth. Certainly within the realm of possibility of a snow leopard kill. Later, a local reported snow leopard tracks on the road leading to our camp. Trackers dispersed across the valley, scanning the rocky ledges and cliffs with spotting scopes. We sat quietly scanning, until one of the trackers came running down a steep hillside, and delivered the news: a snow leopard.

His (we assumed he was a male, although no one could confirm) kill was located just 150 yards from our camp—a very, very lucky chance occurrence. We watched him for four days, as he stayed to feed on the frozen carcass, fully within view. During that time, we watched patiently as he slept in the sun. And slept in the sun. And slept in the shade! And slept in the sun. Someone always had their eye on the lens, watching. And when he shifted position, we’d yell, “Head up!” and everyone ran to the scopes. He stretched like a housecat, and curled his long tail around him, using it as a pillow. We’d squeal and coo, like children. We’d celebrate every evening with a toast of cheap brandy, before heading to bed at 8pm. We became compatriots in battle, bound by one, big, fluffy kitty cat.

The trip was 12 days in the Himalayas, split between two locales. We stayed at our tented camp for eight, adjusting the itinerary due to seeing the leopard. We also stayed at a homestay for the balance, where the accommodations were slightly more luxurious, but still with limited heat, and no indoor plumbing. At the end of the trip, we said good-bye to the local guides and staff (five of them), and the couple from Spain (who were the only paying tourists other than me) departed. My tour guide, Marta, and I headed onto Talla and Bandhavgarh to search for tigers. The accommodations there were absolutely luxurious with toilets and showers, a real bed, and a space heater. And the climate was balmy at 55-65 F. We had an amazing day and a half exploring Bandhavgarh Tiger Preserve, where 65 tigers reside in 172 square miles. Chances of seeing tigers is slightly better than seeing snow leopards in Leh, yet we saw only one, and only for five minutes.

Even so, my trip was blessed with wildlife. Everyone we talked to spoke of how lucky we were. Most people see a snow leopard on our itinerary, but they are usually much, much further away, and for only a few minutes. We saw two (the second was just a brief interlude—a more typical tourist experience), and we saw a tiger.

I like to think this luck was a reward for my bravery. For not cancelling the trip when I couldn’t find a travel partner. For not chickening out--knowing that I get cold very easily and don’t like curry (especially now!). And it reminds me that good things generally come from sticking your neck out.

For many years, my annual reviews at PGAV consistently pointed to one major downfall of my performance: not being assertive enough. I realized in India—as I pondered if I really knew how to identify frostbite—that I had become quite assertive. I ‘stopped asking for permission, and started asking for forgiveness.’ And many times I failed, but many more times, I didn’t. It was more than not failing. It was succeeding. Taking chances and not waiting for the “perfect time” has changed my trajectory in my professional life. I always think about design from the options that we haven’t yet tried. I explore the crazy ideas that seem, on first glance, unrealistic. I don’t back away just because there is a potential negative—because there might also be a bigger positive you don’t yet see. However, it doesn’t mean we waste time going in never-ending circles. I’ve become strong enough and brave enough to make decisions based on logic, reasoning, and a little gut—and run with them.

And you should too. Step out into the cold, or into a room full of strangers, every once in a while. Speak up. Take action. Take a chance… and maybe you, too, will be blessed with big cats.

The New Zoos: Designing Spaces With Animals in Mind

I was recently interviewed for an article about the complexities of zoo design especially in relation to animals' needs. It's a great article on VetStreet.com. Check it out!

How to Become a Zoo Designer

Each week, I receive at least one email from an enthusiastic young soul asking for advice on how to become a zoo designer. Many requests are from college students, already several years into design school. Others are from enterprising high schoolers (and a junior high schooler or two) planning their futures. I've even corresponded with several mid-career adults, looking for guidance on how to change career paths. Every one of them (and, I assume, you, too!) are passionate about animals and seek to share that passion with zoo guests--to help them create connections to wildlife and become advocates for our natural resources. That's very admirable. That's where I started (and what keeps me energized), too.

But, let's talk some realities. As a zoo (and / or aquarium) designer, you will likely work for a private design firm, not a zoo. Zoos these days are starting to understand the value of on-staff designers, but the reality is, very few zoos actually have them; and more often than not, they do very little actual design work, or are relegated to small projects such as signage, snack stands, or demonstration gardens, leaving major capital projects to licensed architectural firms with greater resources. These zoo positions are usually most valuable as client representatives during the design and construction phases, acting as go-betweens (and sometimes decision-makers) for the zoo administration when communicating to designers and contractors. I do believe we will see an increase in these types of positions becoming available, though, as institutions realize the value of having staff that truly understand and are highly literate in design and construction--they can provide great insight to their consultants about the zoo itself, local regulations, and increase the efficiency of communication between consultants and staff, not to mention the fact that they understand drawings and help prevent issues down the line thus ultimately saving the zoo money.

So, let's say you're ready to get a job with a firm. Where do you start? Within the U.S., three major firms specialize in zoo and aquarium design (depending on how you define 'major'), and are generally the three competing for the major projects: Portico Group is in Seattle; PGAV Destinations is in St. Louis; CLR is in Philadelphia. Beyond these three, there are about 10+ small and medium firms, ranging from <5 staff to about 30 staff, located around the country that have completed zoo / aquarium design work, or specifically specialize in such. Seattle is a hot bed of activity due to "patient zero" Jones & Jones, from which most, but not all, firms that specialize in zoo design spawned. Wichita, New Orleans, and Boston are home to several others. If you decide you want to be a zoo or aquarium designer, you will likely live in one of these cities. I hope that's okay.

You've gotten a job! Congratulations! You've moved in, you're ready to go. Now what's the day to day for a zoo designer? Likely the first few years will be painful. Trust me. It's not what you expect. You'll have long hours (50-60+ hour weeks regularly) staring into the abyss of the computer, drawing things that someone else designed. Figuring out the details like the hinge on a gate or how to downspout a thematic wall. You likely will not do site visits or even be able to meet the clients for several years, until you've proven your worth. You may be shuffled from one project to the next without seeing a project from start to finish, often juggling multiple projects at once. But, it does get better, although not much more glamorous! When you do finally reach the point in your career when you get to visit the zoo you're working singularly for, you generally only get to see the inside of a conference room on a quick one or two day trip--where you'll spend the evening working in your hotel room on drawings that you didn't get to complete because you spent the whole day inside that conference room.

Still interested? Yes? Okay--let's get to what you really want to know: How do you become a zoo designer?

I wish there was a magic answer to this. There is no school of zoo design. No specific university, no highly specialized curriculum. Right now, if you want to become a zoo designer, you have to do it of your own accord. Most of today's successful zoo and aquarium designers fell into their jobs. They may have done a college project or volunteered at their local zoo, but the vast majority became zoo designers by dumb luck. They were architects or landscape architects that happened to work at a firm that happened to get a zoo project, and over time, one project became many. Before they knew it, they were experts. But, the fact that I get so many inquiries is telling me this is slowly changing. As zoos evolve, and exhibits become more engaging, young people are realizing the potential for design careers focused entirely on zoos and aquariums (museums and theme parks, too!). This will lead to more and more students with specialized experiences and focused educations. So how will you stand out??

Here are the basics I recommend:

Two degrees: Architecture or Landscape Architecture AND Zoology / Biology / Animal Sciences. It does not matter which design field you choose. The majority of the early design firms specializing in zoo design were traditionally landscape architects. That has changed. Architecture and landscape architecture are inextricably integrated when it comes to zoo design. Of course, if you are more inclined to design for aquariums, choose architecture. But if you want to design only for zoos or for both zoos and aquariums, go with what is more appealing to you. Do you like to design structures? Or are outdoor environments more appealing to you? Go with what will be most interesting to you. As for the science degree, this is not required, but is very appealing to employers. This will set you apart from other design-only students. You could also just get a minor, but doing so will be very challenging, as zoology is a highly rigorous degree while design school is extremely time-consuming. It is possible, but it will not be fun.

Focus every project where you have a choice of topic on zoos or aquariums. Believe me, it will be a challenge. You will get a lot of push-back from design profs wanting to encourage you to expand and explore. Go ahead, but if you truly believe you want to design zoos, you'll want every opportunity possible to explore this complex field.

Get an internship at a zoo / aquarium. Doing anything. You don't have to have a design internship. Repeat. You do not need a design internship at a zoo. You do need behind-the-scenes experience. Do an animal care internship. Do a marketing internship. Do whatever kind of internship you can get. You will need to understand every aspect of zoos in order to design effectively for them.

Get an internship at a ZOO / AQUARIUM design firm. Do not just get an internship at the local architecture firm near your university. This is a chance to see how zoo design really works, and get your foot in the door to one of the very few specialist firms in the country. While you are there, work hard. Ask lots of questions. Share your passion. We remember it when it comes time for you to send in your resume after all those years of school.

Research and network on your own. Visit zoos and aquariums as often as possible, attend AZA conferences, visit zoo design firms, get to know designers, get to know your local zoo. Basically, ask loads of questions, read as much on the topic as possible, get tours and behind the scenes as often as possible. Learning on this topic is not going to happen in school. You have to spend your own personal time researching and educating yourself.

One of the wonderful things about the zoo and aquarium industry is that most people involved are kind and willing to help, if you ask. Zoo and aquarium personnel are in it for

the love of animals, and usually are more than happy to answer questions or direct you to someone who can. I had a lot of great people help me get to where I am today, and hopefully, I can repay their kindness by helping others on their own journey. As always, if you have any questions or need advice, just ask.

If you'd like another zoo designer's opinion, check out Jon Coe's paper on how to become a zoo designer. There is definitely much overlap!

Good luck!!

Underdogs: The Appeal of the Small Zoo

I’ve always been partial to the underdog. Those whose beliefs and perseverance outweigh the skeptics' might by shear doggedness and tenacity. Those tirelessly working to do right despite just scraping by. I’m one of those people who gladly buys the opening band’s CD despite not having anything on which to play it. I always choose a local restaurant over a chain. My March Madness bracket is upset city, and I never liked that Michael Jordan.

The same is true for zoos and aquariums. Don’t get me wrong…I love the big guys and the top-notch experiences they offer. Their excellence in care, leadership in conservation and education, and ability to fill a day with shows, thematic exhibits and fun activity; the star species and large, diverse collections they maintain.

But there’s just something about the little guys. The ones caring for an oftentimes misfit collection of domestic goats, non-releasable hawks, three-strikes bears, confiscated leopards and donated snakes. Those whose skeleton staff, supported by an army of volunteers, work 18 hour days and happily offer up their own home as an impromptu nursery or quarantine area. Those zoos and aquariums whose budgets for capital improvements over the next 15 years barely equal the cost of a single exhibit at a world-renowned counterpart. The little guys. The underdogs.

So what constitutes an underdog zoo or aquarium? It’s something I’ve been thinking about a lot lately, but on which haven’t truly come to a conclusion. There’s something about its physical size—probably less than 35 acres; something to do with its attendance—maybe less than 100,000 annually; gotta’ include its capital expenditures, its market reach, its operating costs, its staff size and its collection size. But, really, there’s always going to be exceptions. What it comes down to is the feel. Just good ole’ fashioned, gut feeling. Like U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stewart famously said, “I shall not today attempt to further define {it}…But I know it when I see it.”

My love affair with the little guys probably began with my first real zoo job. I spent an undergrad summer bumbling through the construction of a Colobus monkey exhibit, part of the huge Africa expansion at the Binder Park Zoo. Flummoxed by construction documents my zoology classes hadn’t prepared me for, I found myself wandering the existing zoo grounds during lunches or after quitting time. I remember most the intimacy of visiting prairie dogs, digging through their dirt pile exhibit, interacting with the talking ravens, housed in a welded wire mesh aviary, and the simple beauty of exhibits carefully located between the towering old growth trees of the Michigan zoo’s deciduous forest. Even with the expansion, this zoo’s character is that of a walk in the woods; the African hoofstock and giraffes wandering the plains of a meadow that just happened to be there.

Similarly, the Central Florida Zoo, located just outside theme park mecca Orlando, takes advantage of its site to create more of an enhanced nature walk than the in-your-face, wholly man-made sensibility of a larger zoo. Rusticity is embraced and forgiven in a setting where you might expect to spot a free-ranging and truly wild alligator or Florida panther lurking in the swampy woods of the zoo grounds. This is a place where you know—from the moment you pull into the vehicular approach surrounded by the tunnel of live oaks dripping in Spanish moss-- to slow down, to take your time. You can see it all and do it all. There’s simply no rush.

Despite the Central Florida Zoo’s lack of both pathway hierarchy and organization based on distinctly defined regions (which do in fact seem to be defining characteristics of a small zoo), you won’t get lost. And so what if you pass by the porcupine exhibit two or three times in order to see the whole zoo. He’s sleeping conveniently in a location where you can get a good, close look at him. From the gravel parking lot and train ride outside the zoo gates to the elaborate spray pad surrounded by shaded seating, this zoo is quaint, and filled with an unmistakable sense of community. In this region, so ostentatiously built for tourism, this little zoo provides an escape to normalcy and a place for residents (and tourists alike) to enjoy a quiet afternoon in nature with family.

Perhaps the most meaningful zoo design experience I’ve had is with the Big Bear Alpine Zoo. PGAV’s partnership with the struggling Moonridge Zoo (as it is formerly known) began way back in 2005 when we interviewed in the beautiful San Bernardino Mountains in southern California. The existing zoo, which was the result of many years of dedicated work rehabbing the regions’ animals devastated by negative human interactions, is located on 2 acres in the parking lot of a local ski resort. The animals living here are non-releasable rehabs and confiscations, like Yoda, a Sawet owl, whose wing was amputated after being hit by a car. The animals are well-cared for, but the physical Zoo itself does not reflect the level of care and the conservation / education significance of the facility. Exhibits are chainlink and welded wire, crammed one after the other into its two acres.

We were hired to create a master plan and eventually to the design a wholly new zoo on a larger site, but still on a tight budget. And over the years, we’ve watched as the community support for the project has grown--despite bumps in the road. One day, the new zoo will be complete; the animals will have spacious new homes, the visitors will have an enriching experience, and I’ll be absolutely humbled to have been a small part of making a difference for such a worthwhile institution.

So, for me, the appeal of small zoos and aquariums stems from the fact that it seems, as designers, we can affect change the most at these institutions. These are facilities which rarely have capital for major physical changes. Places with big visions, but limited resources. These facilities need master plans not only for fundraising and planning purposes, but for the team building and strategizing they provide—for clarity of vision. They need experienced consultants that can offer creative and low-cost solutions to design issues; provide guidance on guest experience. Oftentimes, simple changes drastically affect the public perception of a place —and sometimes just the act of planning itself illustrates such commitment and resolve to achieve more that the zoo is elevated in the public’s eye. Many of today’s powerhouses began as just ‘a small zoo,’ but with the support of the community, were able to grow slowly and steadily over the years.

Do not overlook the little guys. Especially the little guys who’ve made the extra effort to become accredited by the AZA (or EAZA, IMATA, or AMMPA). This is an amazing feat for an institution of any size. And as we know, underdogs can impact the world just as mightily as the conventional leaders. We just need to give them a chance.

Why Master Plan?

A few months ago, I visited with a potential client--who will remain unnamed-- dealing with a complicated case of left-overs. An older institution with aging and non-immersive exhibits, a disconnected and fragmented campus, and plans in the works for a sister institution. As we toured the facilities, the director, aware of experiential and logistical issues of his multi-faceted campus, asked how I could help with one specific exhibit. I smiled and indulged him in some top-of-the-head design suggestions about visibility and theming, but ended by asking, “And what are your plans for this space?” (indicating the mostly unused plaza surrounding the exhibit). “Well, we’re not sure. We want to change it all. Eventually.”

I dropped my notebook to the floor and screamed, “Stop! Don’t touch this exhibit until you develop a master plan!” I didn’t really do that. But I wanted to.

What I did do was explain the importance of master planning. Master plans are essential to the long-term success of zoos and aquariums. They are tools for exploring and pinpointing issues. They are compasses to keep your staff on track. They are road maps for the future.

But why, you ask. Why do we master plan?

To answer the why, let’s look at the how. Generally, master plans are led and completed by zoo designers, and should include three parts: Analysis, Product Development and Implementation Planning. Each phase sets the stage for the next.

In Analysis, we look at as many aspects of the park as possible, from your market and penetration to building condition. We pour over visitor surveys, attendance and revenue records. We inspect each exhibit and every building. We talk to staff from maintenance to keepers to administrators. We gather and analyze, zeroing in on things that you’re doing well and things that are issues. At the end of Analysis, we create a set of overriding Goals and Strategies for the extent of the master plan.

The Goals are big. Increase attendance. Become world leaders in conservation. Educate our guests. The Strategies are much more specific—and in direct response to the Analysis.

For example, if our goal is to create a financially sustainable organization, some strategies may include adding a new dining facility, increasing appeal of special events rental facilities, or creating budget-friendly new attractions.

These Goals and Strategies inform and guide the Product Development process; they pinpoint specific tasks to be achieved, specific projects to be created. And in the Product Development stage, we delve into these projects. We brainstorm and explore multiple options for projects—creating many more ideas than what we could feasibly achieve in the master plan period. With these options in hand, we systematically evaluate each through the filter of the master plan goals—which often includes market testing. At the end of the Product Development phase, we’ll have a list of selected projects with conceptual storylines, plans, sketches, imagery and rough estimates.

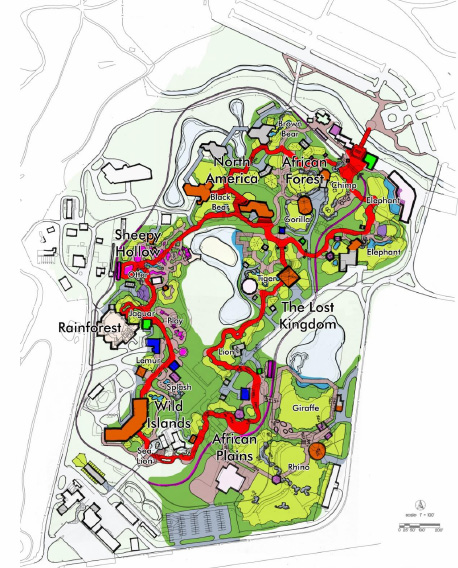

With these projects defined, we finish the master plan by completing an Implementation plan. This phase allows us to understand ‘how’ to get these projects instated. We create a phasing plan—when will each project be rolled out?—and a funding plan—how much capital will the zoo need to raise by what dates? Finally, we create illustrative site plans defining what the zoo will look like at determined intervals (ie every 1, 3, or 5 years).

At the end, the zoo will walk away with a comprehensive plan to achieve specific goals over a set timeline. Generally, master plans plan 10-15 years out. Of course, things come up and even the best laid plans get waylaid. These surprises are exactly why master plans are so important. Because we spent so much time creating the guiding Goals and Strategies, any new issue that comes up should be tackled through the same lenses as the planned projects. Of course, Goals and Strategies may be adjusted over the years, but if the zoo finds their strategic outlook has changed dramatically from the master plan…it’s time to master plan again!

“The Master Plan gave us direction to accomplish these goals and puts us on the path to creating a more enjoyable, interactive and rich experience for the future,” said Stuart Strahl, director of Brookfield Zoo.

Finally, master plans are critical for zoos to move forward—logistically. Through a master plan, zoos have specific projects to show off, to fundraise for. The master plan provides essential visual and verbal descriptions that get the market excited and motivated to give. Not only that, the master plan is a concise definition of who the zoo is (brand today), and where they want to go (brand tomorrow). It’s a great handbook for employees, and a wonderful platform for marketing.

If your zoo doesn't have a master plan, or its master plan is out of date, the best time to start a new one is right now.

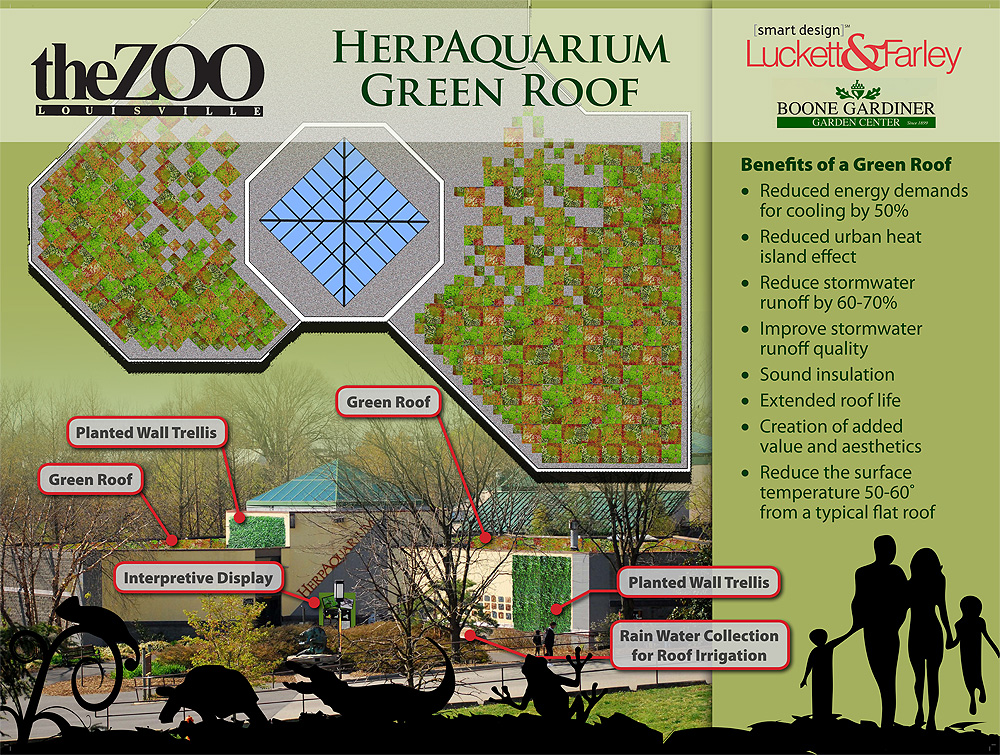

The Greening of Zoos

Recently, the PGAV Specialty Development Team has been spending a lot of time focusing on practical applications of green principles in the complex world of zoos and aquariums. (We have spent very little time looking at aquariums as the amount of energy required to run an aquarium is beyond the practical approaches we are familiar with at our basic level of understanding.) But, nonetheless, zoos are making strides in the green world. And are finally getting recognized for their efforts. In 2010, Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Gardens was named the National Energy Star Greenest Zoo in America for their work including a Platinum LEED building and the installation of solar panels over their parking lot. That same year, the Indianapolis Zoo received a Governor’s Award of Environmental Excellence for their recycling program, and was the first zoo in the nation to receive the EPA’s Green Power Leadership Award for their commitment to purchase electricity created by green means.

But, I was curious. What are most zoos doing these days to become green, or at least, to give the impression that they are ‘going green?’ And, how many of these practices are things that we as zoo designers can positively influence or encourage through design?

Last month, the Zoo Design SDT investigated those questions through a rather admittedly simple exercise: We browsed the internet to find green zoos and their practices.

Each of us collected the green practices of three zoos by searching for ‘green zoo’ on Google, then searching for all of the practices that zoo had published online. We then sorted the practices into general categories, like Sustainable Purchasing, Solar Panels, and LEED Projects.

We quickly realized that these categories fall into two overall groupings: Operational Practices and Physical Plan Components, or “Things we probably can’t affect” and “Things we definitely can affect,” respectively.

After gathering all of these practices, it is abundantly clear that although zoos are making strides to become responsible green leaders in their communities, there is a lot of room to grow. Most zoos have strong recycling and composting programs, have initiated a green purchasing program for zoo products (like compostable or corn based dining wares and recyclable content paper products), and have implemented strategies for decreasing utilities usage (like programmable thermostats and lighting on sensors). But more than that, consistent programs are scarce.

And physical plan green principles are the least implemented thus far. This indicates that although zoos have the best intentions, we have a long way to go, and as zoo designers, we are perfectly perched to help guide zoos through into the next generation of zoo design: Green zoo design.

To review realistic green options for exhibit design, re-check out my previous post "Green Design in Zoos."

What is Bravery?

Yesterday, Wordpress (the website that allows me to bring this blog to you) sent me an e-mail suggesting that I write a post addressing “the bravest thing you’ve ever done.” It struck me that I could apply that question directly to my profession, as often bravery is at the heart of design. To be “brave”, according to Dictionary.com, means:

1. To meet or face courageously: to brave misfortunes.

2. To defy; challenge; dare.

How often do I meet or face courageously? I might generously answer: daily. Some might say just getting out of bed can be an act of courage. But that’s not what we’re talking about here. Daily, as design professionals, we must make decisions. We must choose the width of a path, the height of a wall, the length of a beam. We must decide how to communicate our ideas to our peers and to our clients. We must be courageous to suggest our deepest thoughts to those who are capable of shooting us down with a shake of the head, crushing our hours of glorious contemplation in a split second. We must speak our minds and forge a path. As designers, some might argue, requires courage daily. Not to mention braving misfortunes.

But I’m more intrigued by the second definition. To defy. To challenge. To Dare. How often do we actually reach those lofty heights? How often do we truly put our necks out-- suggest something contrary to our clients’ preconceived notions; contrary to our bosses’ well-intentioned strategies? Not often, I’d guess.

As I’ve said before, design, especially zoo design, tends to push forth, birthing innovation once in a blue moon, only to then regurgitate and spew forth a lesser and lesser version of that once impressive original concept. Instead of continually challenging our designs, instead of continually working to improve the previous iteration, to learn from our mistakes and successes, we far too often just simply pull out examples and drawings from the last time we built that barrier or concepted that raptor exhibit, and copy. Copy. Copy.

So as I consider the question ‘What is the bravest thing I’ve ever done?’ I realize, embarrassingly, I haven’t done it yet.

Multi-Disciplinary Integration...A Mouthful of Fun!

It doesn't exactly roll off the tongue, but multi-disciplinary integration in tourism attractions continues to roll forward as a newly emerging trend. Discussed before purely as the evolution of 'science-based institutions', this trend is finding its way into all forms of tourism destinations.

Consider Atlantis Resort in the Bahamas and Dubai. Not only are these places over the top resorts with beautiful beaches and luxurious appointments, but they've integrated a themed water park as well as an aquatic life park into their campuses. Aquariums are found throughout the properties, and not just typical ho-hum aquariums either; we're talking Aquarium! aquariums. Much like Discovery Cove, visitors can take part in swimming with dolphins as well as enjoying other animal attractions, such as a shark tank and jellies. They've taken a resort and integrated a science-based institution. However, Atlantis is not the focus of this post.

Recently, in my work, we've been spending a lot of time making fun and beautiful places without stepping back to realize what it is we're really doing; without taking time to truly translate our actions into theory from which everyone in our profession can learn. That is what this post is about. Refreshing our memories about multi-disciplinary integration.

Its happening all around us. Theme parks more seriously integrating conservation issues. Zoos incorporating science-center interactives which are about more than just the size of a polar bear's paw. Aquariums introducing land-based animal habitats. Subtle changes, yes, but all moving toward the ultimate in end goals...creating a one stop shop for science, education, AND entertainment. However, in the end, I do believe these institutions will filter out into two sects: those based on science and education (ie zoos and aquariums now), and those based on play (ie theme parks and children's museums now).

Some thoughts on what we'll see in the coming years:

Zoos (and possibly aquariums) utilizing gentle, family ride systems to introduce new ways to experience animals

More Atlantis-style resorts with focus on conservation and local habitats, including breathtaking animal habitats presented in ways not seen in zoos and aquariums

Science centers across the board becoming Life Science centers by including animal exhibits

Theme parks spending millions to incorporate Educational elements, either as stand alone attractions or as enhancements to rides and shows

Jacksonville Zoo recently opened a new attraction, Asian Bamboo Garden, being touted as a 'garden' first, and 'exhibit' second. The attraction features nearly 2.5 acres of Asian gardens, with a small Komodo dragon exhibit tucked away into one corner. The Zoo focused on botanicals for this project, rather than zoological. This is rather extraordinary, if you think about it. Concept design always begins with the question: What's marketable? Projects are built to get folks through the door. Jacksonville is saying with this project, gardens are profitable. Generally, to me, zoos that call themselves 'zoos and botanical gardens' do so simply because they have beautiful grounds, not because they ever intend to add new attractions based on gardens. However, Jacksonville Zoo and Botanical Garden has done just that, truly illustrating a multi-disciplinary integration in the direction of science.

And, finally, Columbus Zoo. Through a series of moves that appears to be an effort to shift almost 180 degrees from a science-based institution into a mini-resort, the Zoo has announced the initiation of a feasibility study on adding a hotel to the already massive complex. Recently, the zoo added a golf course and a water park (check out their fun website). Considering the Zoo is actually a zoo and an aquarium, the complex is quickly becoming a major multi-disciplinary destination, with the focus shifting from science to play. Columbus Zoo again illustrates the emergence of multi-disciplinary integration. I'm extremely confident that as we move forward in the evolution of science-based institutions, we'll see many, many more of these kinds of integrations.