Each week, I receive at least one email from an enthusiastic young soul asking for advice on how to become a zoo designer. Many requests are from college students, already several years into design school. Others are from enterprising high schoolers (and a junior high schooler or two) planning their futures. I've even corresponded with several mid-career adults, looking for guidance on how to change career paths. Every one of them (and, I assume, you, too!) are passionate about animals and seek to share that passion with zoo guests--to help them create connections to wildlife and become advocates for our natural resources. That's very admirable. That's where I started (and what keeps me energized), too.

But, let's talk some realities. As a zoo (and / or aquarium) designer, you will likely work for a private design firm, not a zoo. Zoos these days are starting to understand the value of on-staff designers, but the reality is, very few zoos actually have them; and more often than not, they do very little actual design work, or are relegated to small projects such as signage, snack stands, or demonstration gardens, leaving major capital projects to licensed architectural firms with greater resources. These zoo positions are usually most valuable as client representatives during the design and construction phases, acting as go-betweens (and sometimes decision-makers) for the zoo administration when communicating to designers and contractors. I do believe we will see an increase in these types of positions becoming available, though, as institutions realize the value of having staff that truly understand and are highly literate in design and construction--they can provide great insight to their consultants about the zoo itself, local regulations, and increase the efficiency of communication between consultants and staff, not to mention the fact that they understand drawings and help prevent issues down the line thus ultimately saving the zoo money.

So, let's say you're ready to get a job with a firm. Where do you start? Within the U.S., three major firms specialize in zoo and aquarium design (depending on how you define 'major'), and are generally the three competing for the major projects: Portico Group is in Seattle; PGAV Destinations is in St. Louis; CLR is in Philadelphia. Beyond these three, there are about 10+ small and medium firms, ranging from <5 staff to about 30 staff, located around the country that have completed zoo / aquarium design work, or specifically specialize in such. Seattle is a hot bed of activity due to "patient zero" Jones & Jones, from which most, but not all, firms that specialize in zoo design spawned. Wichita, New Orleans, and Boston are home to several others. If you decide you want to be a zoo or aquarium designer, you will likely live in one of these cities. I hope that's okay.

You've gotten a job! Congratulations! You've moved in, you're ready to go. Now what's the day to day for a zoo designer? Likely the first few years will be painful. Trust me. It's not what you expect. You'll have long hours (50-60+ hour weeks regularly) staring into the abyss of the computer, drawing things that someone else designed. Figuring out the details like the hinge on a gate or how to downspout a thematic wall. You likely will not do site visits or even be able to meet the clients for several years, until you've proven your worth. You may be shuffled from one project to the next without seeing a project from start to finish, often juggling multiple projects at once. But, it does get better, although not much more glamorous! When you do finally reach the point in your career when you get to visit the zoo you're working singularly for, you generally only get to see the inside of a conference room on a quick one or two day trip--where you'll spend the evening working in your hotel room on drawings that you didn't get to complete because you spent the whole day inside that conference room.

Still interested? Yes? Okay--let's get to what you really want to know: How do you become a zoo designer?

I wish there was a magic answer to this. There is no school of zoo design. No specific university, no highly specialized curriculum. Right now, if you want to become a zoo designer, you have to do it of your own accord. Most of today's successful zoo and aquarium designers fell into their jobs. They may have done a college project or volunteered at their local zoo, but the vast majority became zoo designers by dumb luck. They were architects or landscape architects that happened to work at a firm that happened to get a zoo project, and over time, one project became many. Before they knew it, they were experts. But, the fact that I get so many inquiries is telling me this is slowly changing. As zoos evolve, and exhibits become more engaging, young people are realizing the potential for design careers focused entirely on zoos and aquariums (museums and theme parks, too!). This will lead to more and more students with specialized experiences and focused educations. So how will you stand out??

Here are the basics I recommend:

Two degrees: Architecture or Landscape Architecture AND Zoology / Biology / Animal Sciences. It does not matter which design field you choose. The majority of the early design firms specializing in zoo design were traditionally landscape architects. That has changed. Architecture and landscape architecture are inextricably integrated when it comes to zoo design. Of course, if you are more inclined to design for aquariums, choose architecture. But if you want to design only for zoos or for both zoos and aquariums, go with what is more appealing to you. Do you like to design structures? Or are outdoor environments more appealing to you? Go with what will be most interesting to you. As for the science degree, this is not required, but is very appealing to employers. This will set you apart from other design-only students. You could also just get a minor, but doing so will be very challenging, as zoology is a highly rigorous degree while design school is extremely time-consuming. It is possible, but it will not be fun.

Focus every project where you have a choice of topic on zoos or aquariums. Believe me, it will be a challenge. You will get a lot of push-back from design profs wanting to encourage you to expand and explore. Go ahead, but if you truly believe you want to design zoos, you'll want every opportunity possible to explore this complex field.

Get an internship at a zoo / aquarium. Doing anything. You don't have to have a design internship. Repeat. You do not need a design internship at a zoo. You do need behind-the-scenes experience. Do an animal care internship. Do a marketing internship. Do whatever kind of internship you can get. You will need to understand every aspect of zoos in order to design effectively for them.

Get an internship at a ZOO / AQUARIUM design firm. Do not just get an internship at the local architecture firm near your university. This is a chance to see how zoo design really works, and get your foot in the door to one of the very few specialist firms in the country. While you are there, work hard. Ask lots of questions. Share your passion. We remember it when it comes time for you to send in your resume after all those years of school.

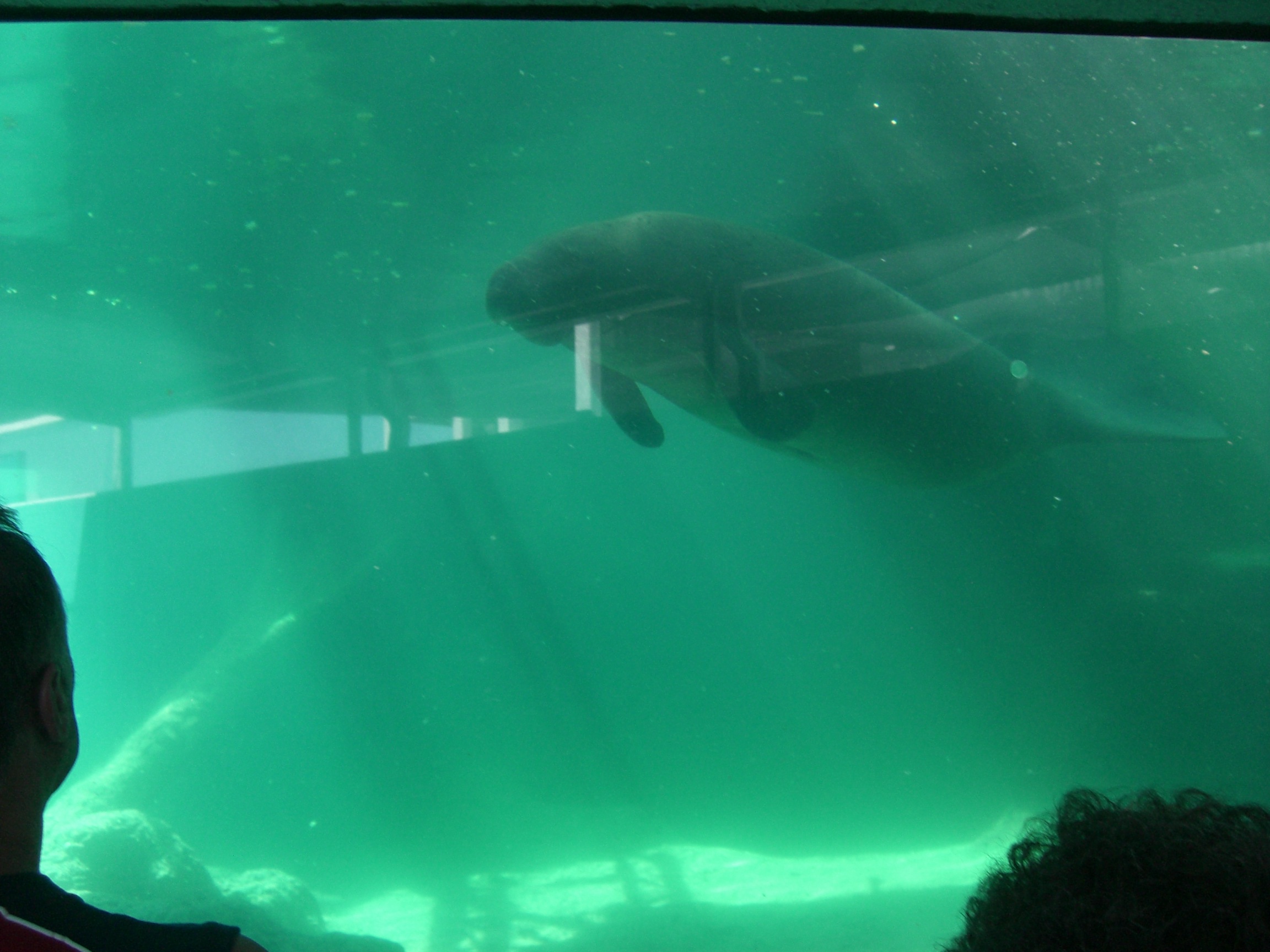

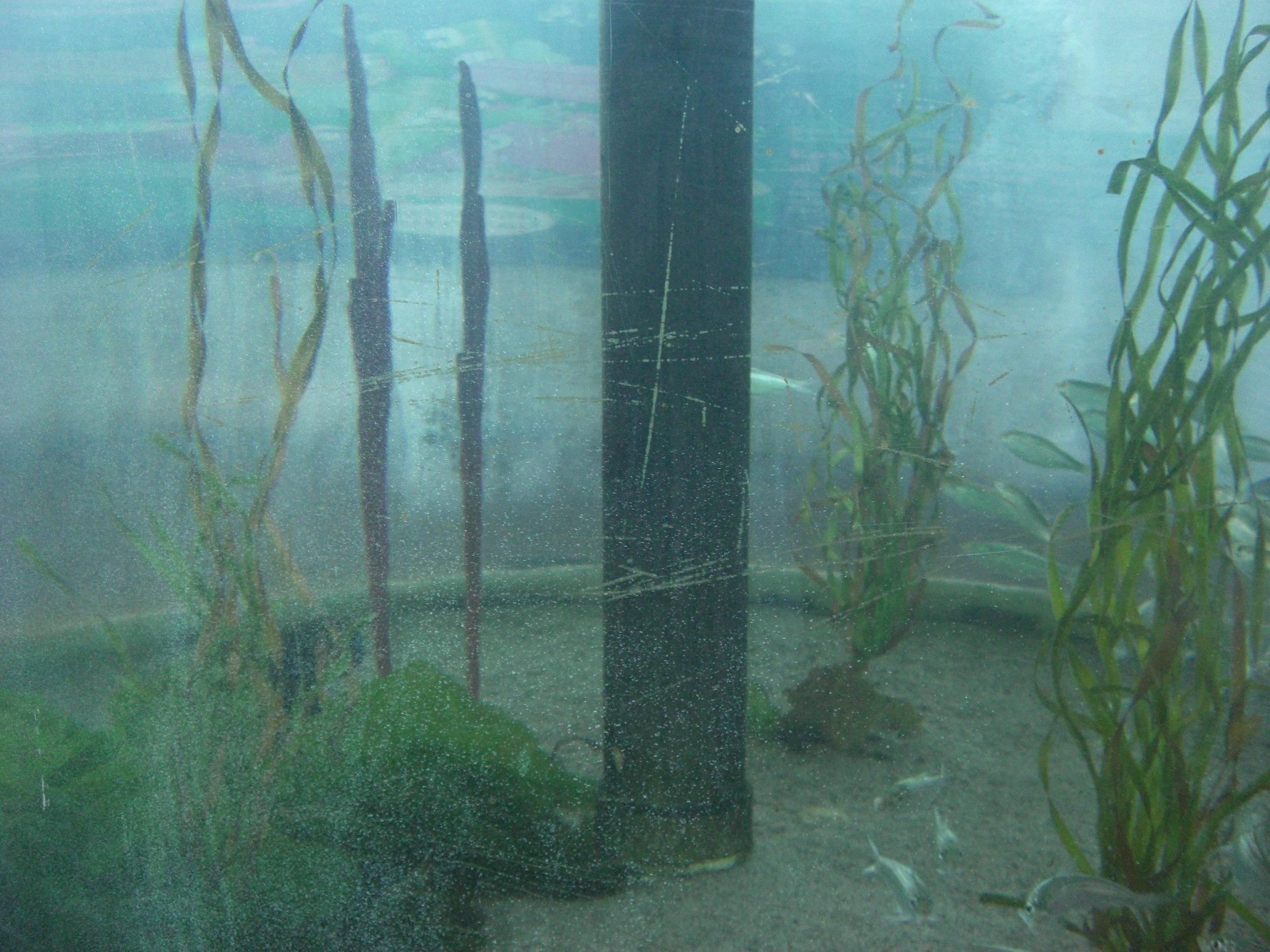

Research and network on your own. Visit zoos and aquariums as often as possible, attend AZA conferences, visit zoo design firms, get to know designers, get to know your local zoo. Basically, ask loads of questions, read as much on the topic as possible, get tours and behind the scenes as often as possible. Learning on this topic is not going to happen in school. You have to spend your own personal time researching and educating yourself.

One of the wonderful things about the zoo and aquarium industry is that most people involved are kind and willing to help, if you ask. Zoo and aquarium personnel are in it for

the love of animals, and usually are more than happy to answer questions or direct you to someone who can. I had a lot of great people help me get to where I am today, and hopefully, I can repay their kindness by helping others on their own journey. As always, if you have any questions or need advice, just ask.

If you'd like another zoo designer's opinion, check out Jon Coe's paper on how to become a zoo designer. There is definitely much overlap!

Good luck!!